A Loud and Colorful Advance Party Marks the End of Hogle Sanctuary's Winter Silence

The time has come to commemorate and then dismiss the just-departed “Silent Winter” of '018-019 (apologies to the late, great Rachael Carson). This was a season that appeared naturalistically barren from my Hogle Sanctuary vantage point. Silent and barren, that is, in contrast to my previous 2 Hogle winters, which, despite fallow periods, dished up sporadic Eagle fly-overs and skirmishes, plus cameos by Cormorants, Marsh hawks, assorted gulls, beached Snapping Turtles, Beaver, Muskrats and Squirrels, while providing an intermittent auditory backdrop of squawks, chitters squeaks, caws, jeers and rat-a-tats. Such sensory rewards were sparse for me this time around.

Finally there are signs that the figurative bird repellent is beginning to wear off. Vultures appeared in Sanctuary and town skies in the 2'd week of March, and quickly became a welcome, if delayed roosting presence on both north and south ends. Robins migrating from southern climes recently joined the sparse but rugged group of over-wintering companions on the scene. For me, though, Hogle's silence ended definitively (and literally) on the morning of March 17, St Patrick's Sunday. I parked by the Sanctuary's Eaton Avenue entrance under partly sunny 9:30 AM skies and started down the trail toward the boardwalk and viewing area. As it developed I had to give up my descent at the top of the riser zone and survey the boardwalk, the massive old cement pump station, and some of the waters from on high. The most traveled part of the Eaton trail has recently been, and remained on that day a treacherous packed-down strip of ice. The remnant of once- navigable snow alongside the trail has also been largely iced over. The Eaton approach still remained tricky as recently as March 21 though the risk factor may by now have given way to the mere nuisance factor of mud season gunk.

The parts of the West River Delta area visible from my perch showed new or widened channels of open water since my last previous visit, but I saw little if any of the ice jam- mediated flooding predicted by some sources. As in other recent visits, no birds or mammals were visible around the trail or below at the boardwalk level, but, encouragingly some caws and a chorus of honks signaled the unseen passage of crows and geese.

Suddenly I was treated to an unmistakable and unexpected spring anthem: a series of loud, shrill, overtone-laden “kon-ka-reeeeee's “, the signature calls of Red-winged blackbirds, filtered down from the Eaton Ave neighborhood I was now returning to. As I emerged from the woods, I was greeted by visual confirmation. Some 12-15 blackbirds were artfully distributed on the barren branches of an Oak or Maple tree in a yard on the east side of Eaton Ave's north-south stretch. Back-lit by the eastern sun, the birds all appeared similarly dark, but occasional flashes of red epaulet combined with continuing vocalizations served to establish that I was viewing a small flock of Red-winged blackbirds.

This was exciting to me, in that Red-wings are among the most visually striking, and entertainingly aggressive of all spring harbinger species. The fact that they are also voraciously insectivorous is both encouraging (their efforts will be appreciated very soon, when mosquitoes and flies make their appearances) and perplexing, in that their favored prey insects were not yet obviously there for them as they huddled in the 31F chill. One assumes that the Red-wings must have known what they were up to, though they have not been sighted since that Sunday, neither by me nor by residents whom I buttonholed. Let's hope they're holed up in some life-sustaining local haven or have found well-stocked bird feeders.

Red-wings are great favorites of mine, in part because of their vivid looks (that is the males' epaulet-flashing sinister good looks; the females are tastefully brown-mottled with a subtle russety suggestion on the tips of back feathers) , remarkable vocalizations and consumption of nuisancy insects, and in part owing to the manic, shrill high-energy ferocity with which they defend their territories and nests against any and all intruders. An anecdote from Chicago days 3 decades ago serves to illustrate. Strolling through Lincoln Park, a prosperous, neighborhood often referred to as a “yuppie town”, and specifically through the Lincoln Park Zoo on a glorious warm spring morning, I came upon a knot of people, many resplendent in Sunday morning finery, gathered around a Tapir's outdoor stomping ground. It was quickly evident what had attracted these folk's attention: the Tapir, a large, sturdy, and as it developed, studly male, was experiencing the glandular surges of spring in a distinctively masculine way. One after another, would-be passers-by of various genders and ages joined the clutch of gawkers captivated by the beast's equine-scale endowment. So awe-struck were they, that they were unaware, at least initially, of the entry of another testosterone-fueled character onto the stage: a furious male Red-wing. Enraged by the proximity of the human gaggle to his and his mate's nest in a nearby tree, he first circled the group screeching avian expletives. Then as his ire escalated, he started dive-bombing people's heads, especially ladies' up-do hairstyles and Easter season hats. By the time the crowd dispersed, some members having left to avoid avian strafing runs, others as the tapir's rampancy gradually waned, the Red-wing had knocked a hat off one woman's head and disarranged a couple more.

As equal opportunity aggressors Red-wings also mob raptors who pose a threat or anger them in any way. In fall of 2017 I saw a Red-wing give continuous chase to a Turkey Vulture for over 10 minutes, flapping mightily to keep pace with the soaring buzzard as the birds made at least two tandem aerial circuits; each roughly from above Hogle Sanctuary's boardwalk area, north over Putney Road beyond the Auchobon plaza, then west to the I 91 bridge area, southeast to the Retreat Meadows Pond and back to the boardwalk again.

I chide myself for having been excited and, for, let's face it, for enjoying these aerial dramas, given that they entail great distress for the Red-wings and exact a massive energetic cost; however I can't seem to help being enthralled, and I DO admire the birds' no-holds-barred derring-do. Red-wings are among the few species that out-rank my beloved Northern Mockingbirds in terms of fearless aggression in defense of nest and hatchlings; they even rival the legendary exploits of nesting terns in attack mode.

Given their operatic scale presence, striking looks, unique calls and verve, Red-wings seem to me to be eminently deserving of a signature flock name: something to compare with murders of crows [and parliaments of English crows], gaggles of geese, kettles of hawks, murmurs of Starlings [a new one on me] - not to mention schools and pods and prides and etc. A list of candidate names could include a "shrill" of, "shriek" of , "overtone" of, "squadron" of, or “dive-bomb” of Red-wings. You're invited to weigh in with your candidates as well as to consider names for groups of other familiar birds, such as cackles of nuthatches, scolds of wrens or robins, imprecations of jays, gobbles of Wild Turkeys, rattles of kingfishers ( if kingfishers ever flock).......

On that note, I wish you all and the early-arriving mini-shriek of Red-wings a happy and prosperous Spring of 2019.

An Austere Hogle Sanctuary Sleeps in Beneath a Chill Sunday Morning Sun

Fall had recently passed its halfway point this November Sunday, and the pending onset of winter appeared to permeate the Hogle Sanctuary as I headed down the Eaton Ave approach. A dense carpet of fallen leaves scrunched underfoot: richly yellow maple increasingly peppered with fading brown oak. As I reached the riser zone's new-ish cement “stairs” leading down to the water-level boardwalk, the vivid green of grass seeded in the trail area during late summer renovations stood in marked contrast to the flat browns and grays of withered brush flanking the trail. A thin coating of frost on the boardwalk slats reflected an 8:45 AM temp of 34F, and puddled water lay beneath and well “inside” the boardwalk attesting to the past week's rains and wind. The oak brown-intensive remaining leaf cover on slopes to the west and north of the Sanctuary's observation zone was dulled and chilled down to a drab matte finish reflecting metabolic shutdown. The Sanctuary's perennial scenic beauty was well-launched into somber seasonal lock-down phase.

Visible avian life was limited to one unidentifiably tiny bird flitting between distant trees, and a few small ducks distant in the Meadows pond, possible Buffleheads or Hooded Mergansers. Conspicuously absent were the migratory lallygaggers still on display in October: straggling robins, goldfinches, catbirds, kingbirds/flycatchers, confusing fall thrushes, swallows, blackbirds and etc. Vultures (including Black Vultures, see below) appear to have started their south-bound journeys in the first week of November. Even geese seem to have departed. This morning no cawing crow or jeering jaybird (both of which species are certainly around town) broke into a morning silence profound enough to trigger annoying conscious awareness of my old man's tinnitis. Woodpeckers and classic feeder birds as is often the case, boycotted the Sanctuary in favor of the stately trees and backyard feeders present above near the Eaton Ave trailhead. I had to leave this sere and chilled arena before kingfishers or herons (if any remain) arrived to liven things up.

A couple of of recent recent avian doings merit comment:

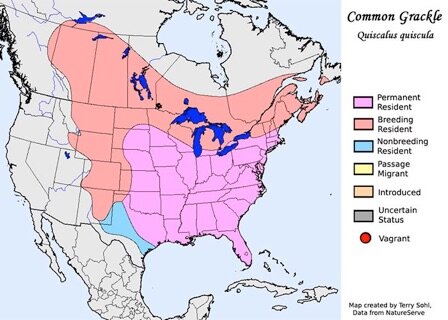

2. I MUST share a demographic landmark that has recently occurred among the area population of Vultures, my Hogle avatar birds ever since their roost trees first drew my attention to the Retreat Meadows shores. The flocks of these ghoulishly fascinating birds that effortlessly cruise the thermals above the entire area, often seen coasting N or S over the Putney RD- Main Street-Canal/S Main corridor, have been and continue to be mainly the familiar Turkey vultures with their 2 tone black and grey underwings, wattled reddish bald heads and pronounced wing uptilt (dihedral) in flight. Note I said MAINLY Turkey Vultures. For the past 2-plus years I've strongly suspected that the other North American Vulture species (other than California Condors), eg, Black Vultures, has infiltrated local populations. Black Vultures grossly resemble Turkey Vultures but differ by being uniformly dark gray to black, save for paler gray (decidedly non-pink) heads and silvery wingtips, are heavier than Turkey Vultures, and have shorter wings and tails. This bulkier build makes flight more laborious for Black Vultures, and soaring, the preferred flight mode for both, is more reliant on strong thermal updrafts.

It's believed that this greater dependence on thermals has been a major contributor to historical limitation of the Black Vulture range to the American South, with few appearing north of the Mason-Dixon line until the 1970s. Recently, though, the Blacks have been moving northward. Around the millenium, breeding populations were documented in MA (1999) and CT (2002). Reported sightings in VT have remained as rare as, ahem, hens' teeth. When Birdwatching in Vermont was published (T Murin and B Pfeiffer 2002), only 5 sightings had been recorded in 115 years from 1884 in Woodbury to 1999 in Colchester, and the only nearby sighting was in 1983 in Vernon.

During my 8 years in VT there have been a handful of reported sightings, mostly in nearby NH. Though I'd personally strongly suspected that Blacks were mingling with Turkey Vulture – dominated area flocks, it was my own viewings of 2 unequivocal Black Vulture solo fly-overs in 2017, followed this Oct 28 by a trio of unambiguous Blacks sailing south over the St Michael Catholic School's Walnut St parking lot, that permit me to state from personal experience that Black Vultures have a real, if sporadic, presence in SE Vermont.

As you're framing the apt question of why anyone should care one way or another about an influx of an intimidatingly large, and arguably ugly avian scavenger bird species, let me counter with a quote from VPR nature commentator/Timber Rattlesnake expert/naturalist supreme Ted Levin. In a 2017 radio piece, Levin summed up his reaction to having seen a Black Vulture above Walpole NH as follows: “Forged in the crucible of sun and rock, black vultures are as moored to thermals as sailboats to wind - held aloft by columns of warm air rising from heated ledges and roads. And any way you look at it, a short-winged, short-tailed, black vulture anywhere near Vermont is a sign of a changing climate”.

To me, as to my illustrious source, Black Vultures are harbingers of largely human-induced climate change that threatens to compromise and ultimately terminate life in/on the global biome: they are out-sized counterparts of coal mine canaries, dusky seaside sparrows and countless other species impacted by mankind's intrusions whose penetrance of VT is a sign of ominous warming trends in the Eastern Seaboard and New England in particular.

This prospect prompts a parting thought; a possible insight about a seeming generational divide in experience of nature. Driving north on I91 a couple of weeks ago, as the sun was about to rise, I was frustrated by my inability to divert my almost 16 years-old daughter's attention from her hand-held electronics to the dazzling sight of a brilliant Hunter's full moon sinking in the west. This non-receptivity was, to me, emblematic of a more general change from her (and many of her peers') early life openness to nature in its many guises to a near-total lack of interest.

I have tended (and still tend) to regard this trend as a sad form of self-deprivation in large part driven by the ever more pervasive and addictive dominance of electronic media in every facet of life. This morning, though, as increasing daylight muted the moonscape, I was struck by the possible import of another disincentive to a deep appreciation of the natural world. If environmental deterioration continues advancing at the rate projected in recent arguably over-optimistic reports, my daughter's generation stands to be, well within normal lifetimes, mired in a disastrously degraded biosphere in which what remains of terrestrial and oceanic plant and animal life, not to mention human life options, will be nothing but depressing, and likely terrifying to contemplate. It is even fair to question whether my continuing receptivity to the “aha” moments of a nature enthusiast is in part made possible by the fact that, in contrast to my daughter's generation, it's unlikely that I will live until the seemingly inevitable time when it becomes impossible to find any pleasure or sustenance in the natural world. Today's youth can hardly be faulted for viewing their nature-loving elders as romantically delusional fossils, not to mention hypocrites who tune out their own culpability in the apocalyptic trajectory of global disintegration. And on that cheery note, I bid you adieu until the next posting.

Blink little fire-beetle, flash and glimmer

For too long I've been laboring over a story commemorating the aberrant whiplash winter of 2017-'018. My attempts to do justice to that season's overabundance of stark departures from any recent winter norms have tied me up in compositional knots. From the historically massive January flooding that inundated the boardwalk area at Hogle sanctuary making it inaccessible by foot for a week or more, to the treacherous snow-topped sheets of shell ice that stretched insubstantially above cavernous vacated spaces after flood waters had receded, tempting foolish traverses that led to break-throughs, to the short but spectacular thaws (high 50s F) that enveloped the entire West River Delta and Retreat Meadows in near impenetrable mists, to the up-the-hill hill onslaught of presumed ravenous beavers who chomped down saplings almost up to Eton Ave residential zone, to the mammoth hit-and-run March blizzard and much more, what a long strange ride it was.

As I reveled in summer blink-fests, a boyhood memory flashed into my mind. Back in the late '50s in the then-somewhat-sleepy and bucolic town of Frederick, MD, I was a member of Boy Scout troop 799 based at Fort Detrick, a decidedly non-sleepy military installation adjoining Frederick's west end. Yes, THAT notorious Fort Detrick, bastion of Cold War – driven biological warfare research; professional home of investigators targeted unknowing as guinea pigs in a nefarious, irresponsible and tragic early CIA test of LSD effects (see recent Netflix offering and earlier episode of Unsolved Mysteries); site of the top-level bio-containment cabinet where a researcher in Richard Preston's best-selling Hot Zone (played by Rene Russo in the film) did or did not infect herself with Ebola virus; and, (despite having de-emphasized biological warfare in favor of the war on cancer by 2001), the putative source of post-9-11 anthrax – contaminated mailings that led to the deaths of 5 addressees and handlers.

In Summer(s) of 1956 and/or '57, Troop 799 scouts became gung-ho participants in a Fort Detrick - sponsored firefly collection drive aimed at purifying and analyzing the enzymes and substrates responsible for the insects' (and their larvaes') remarkable “bioluminescence”, a fascination Detrick scientists shared with peers at major pharmaceutical companies as well as applied and basic academic research labs worldwide. We 11-15 year-olds, oblivious to rationale or consequences or anything but the mad quest, ran amok in yards and fields, feverishly gathering the slow flying and seemingly defenseless beetles in Mason jars. Our tunnel – visioned zeal was such that we raised enough money to support major troop projects, even at what would now rank as a pittance per jar. It barely flickered on our mental screens (or at least mine) that we and other recruited youth groups were severely decimating Frederick's firefly populations for years to come. Not one of my shining moments given that I was embryonically pointed in a naturalistic direction, but then in this pre-Silent Spring era, naturalism was yet to be inextricably linked with species endangerment or other grave ecological concerns.

A future story will deal with profound advances in basic understanding of genetics, metazoan development and other fundamental life processes, as well as strides in medical diagnosis and treatment made possible by use of light signals from purified firefly Luciferase and Luciferin as “reporters” to track the activities of key genes in cells, tissues and even in living creatures in vivo. For now I'll close by expanding on a deliciously gruesome saga of firefly deception and rapacity with which the majority of you are likely familiar: a grisly morsel of Firefly biology that has evoked the richly deserved term “femme fatale”. Read on, and I will dish up what the late, great Paul Harvey might have called: “The REST of the Photuris-Photinus story”.

It has been known for over 60 years that courting fireflies employ patterned exchanges of flashes to recruit partners for mating. Lust-driven males deliver a set number of flashes in a timed sequences, to which the appropriate receptive female responds with a single flash after a precise lag time. Then the 2 flies (generally) rush together, pitch woo, et voila, propagation of species! In the early 1960's James Lloyd, a grad student of the great Cornell entomologist Thomas Eisner' worked out and reported in 1964 a tale of perverted trans-genus firefly lust, deception and rapacity that has captured the public imagination through ensuing decades.

The relatively large females of firefly genus Photuris, Lloyd discovered, sometimes break from nighttime mating dances with Photuris males to enjoy a crispy high protein snack in the form of an unsuspecting (and relatively wimpy) male of a distinct genus, Photinus. The Photuris female uses cruel deception for the purpose. She recognizes a Photinus male's mating flash pattern and sends him a single flash response with the precise timing of a receptive Photinus female. The Photinus suitor then blunders into the sphere of the Photuris “femme fatale” (Lloyd's spot-on descriptor), who immediately gobbles him up with great gusto {nocturnal romantic doings being calorie-intensive ). There's also a reverse twist to this basic trickery: Photuris males sometimes mimic a Photinus male flash pattern in order to simulate an interspecific victim (more enticing than the boring Photuris he is in reality). The Phoinus male thus gains preferred access to his heart's desire, who presumably says “ Aww, whatever, as long as you're here anyway .....”

Now for the REST OF THE STORY, the gist of which is that the benefits Photuris females gain from gobbling up Photinus males transcend mere caloric gratification. Students in Eisner's and collaborating groups discovered in the 70's that some, but not all fireflies are distasteful, emetic or even lethally toxic to various potential predators; as first shown with a lustily insectivorous pet thrush named Phogel, and later demonstrated for jumping spiders, lady beetles, ants, frogs, and assorted lizards. It developed that Photinus 'flies' were potently noxious to predators while some Photuris females and few if any Photuris males shared this repellent trait. Further, a single steroid family chemical closely resembling both the cardiac drug/poison ouabain and a notorious toad venom component (from which it derived part of its name, “luciBUFagins”, (Lbfgn) ). is the predator- defeating agent. In the Photinus/Photuris dyad, Photinius 'flies' of both genders contain epic amounts of Lbfgn and are rejected by predators, Photuris females that have chowed down on Photinus males contain lesser but effective amounts of Lbfgn, while females not having tasted Photinus males, and male Photuris are largely devoid of Lbfgn and are vulnerable to predation.

As you may suspect by now, Photuris females, which are somehow immune to emetic and toxic effects of Lbfgn, assimilate and retain enough of their Photinus victims' supply to make them resistant to would-be predators. A Lbfgn – positive Photuris female clearly needs to make predators aware that she's unpalatable or worse at the very start of a confrontation before sustaining serious damage. She achieves this via a “reflex bleeding” strategy that involves danger-evoked external display of Lbfgn-laced noxious blood droplets.

Australian “bearded dragon” lizards popular as pets in the US, disregard such defensive strategies at their own expense. They unhesitatingly gobble up Lbfgn-positive 'flies'{in relation to which they have no co-evolutionary history, and hence no evolved warning system}. Consumption, of 1 or more Photinus or several Lbfgn positive femme fatale Photuris leads to convulsions, followed within an hour by dramatic skin blackening and death, evidently from rampant tachycardia. But this cautionary case of unexpected consequences of humankind's promiscuous mingling of biologically unprepared organisms as well as the genuine but non-earth-shattering potentialities of Lbfgn as a human cardiac drug go beyond the Harvey-esque “rest of this story”, so at this point I bid you adieu.

“...spanning 6 1/2 to 7 feet”

The Sanctuary has seemed mostly barren during recent visits, but on this late November (27) visit, 8:30- 9:30 AM a chill (25-27 degrees) patchily sunny, with shell ice out to 50 feet whitening in immediate shore area, things were downright lively. As I headed down the trail I was struck again by the contrast between maple oak and nut tree saplings, still tricked out in vividly green leaves while the mature trees towering above them were now stark in their barren-ness.

Chickadees, generally heard but not seen in treetops at the upper trail level were boundng around in the uncut brambles and sagging wildflower stalk remnants that had eluded scorched-earth reaping, while juncos flitted back and forth from under the boardwalk to the surrounding stubble of cut foliage. Dozens of large gulls whose whites and pale grays and dark wing tips best matched Sibley photos of adult non-breeding Herring gulls, though they appeared more massive, on the order of Great Blackbacks flapped restlessly and low all around the area - presumably wondering why, this close to December there are not yet any ice fishermen to pester.

But that's all backdrop -- the big event was the Eagle, the larger of 2 Bald Eagles often on hand of late, making an up-close and personal appearance. There's been upward of 50% chance all Fall long of seeing either of 2 distinguishable Bald Eagles with a sanctuary presence perched on upper branches of trees a couple hundred yards or so out west (towards RTE 30, the Retreat Farm etc) from the nearest possible land vantage point. I'd heard that one or both occasionally perched in the immediate viewing area. I'd not seen this until today though, when, coming down to the boardwalk I was startled by the take-off of an eagle, the bigger of the 2, from a overhead tree perch that had been screened off by thickety twigs and leaf residue. Witnessing the take-off and the flight to a tree a couple hundred feet away on the far side of a narrow channel was thrilling.

Eagles in flight have a presence that is uniquely their own. Watching vultures aloft, for example, one admires their skill and precision, the ease with which they cruise the thermals and breezes, their morbid elegance...... but a big Bald Eagle taking off from nearby is another order of experience - it's magnificent. Whereas Turkey Vultures are impressively massive at 4-5 lb, the Bald Eagle's stately wing beats at take-off are launching twice that weight, some 9-10 lb into the air, 3 to 5 flaps of the elegantly slimmish and pointy wings, spanning 6 1/2 to 7 feet, then a few seconds of perfectly straight winged glide*, then repeat, and away he/she goes.

* This bird don't need no stinkin' dihedral. This bird don't need no updrafts, that's why he/she's still around at end November while the vultures are well into their south-bound journeys, if not at their winter destinations.

Phenomenal creatures, those Bald Eagles.- surveying their dominions with the proprietary, indolent if alert aura of creatures at the very top of the local (or any) food chain at the elevation of their lives. Ben Franklin preferred the seemingly more virtuous and industrious Wild Turkeys over the Bald Eagle as a national symbol. For me, though the visually dazzling, physically overpowering Bald Eagle is the symbol of symbols, I'll take Eagles, laziness, scavenging, low character and all in preference any time. The key question is not whether Bald Eagles are worthy symbols for our once-great country, but whether the USA in its current reprehensible plight deserves a symbol; as magnificent and elegant as the Bald Eagle. How about a Cowbird or Loggerhead Shrike/Butcherbird instead?

A Slow Day at Hogle Sanctuary is Salvaged by a Furry Visitor's Aquatic Star Turn

Finding myself a short mile from Hogle Wildlife Sanctuary with a half-hour to spare at high noon on an intensely sunny Saturday October 14, I made the short hop over to the Sanctuary's Eaton Ave entrance. It was a day for chipmunks to make their presence known - they escorted me to my parking place, scurrying across the street in front of me every 50 feet or so, tails hiked up above their tiny bodies, then scolded me from the trees along the trail down to the water level. A couple of chipmunk burrows that appeared near the step-like “risers” of the path itself in late September and have sometimes shown signs of being beaten down by the human foot traffic, displayed freshly cleared entrances.

The endlessly blue skies were as free of soaring birds as they were of clouds, and devoid of the usually reliable blackbirds and grackles (the swallows, swifts, waxwings, catbirds, goldfinches, flycatchers, hummingbirds and trail-side robins having been absent for weeks). No herons or egrets were visibly stalking or standing locked in mime-like immobility in search of fish, no Belted Kingfishers were seen or heard, the Sanctuary's Bald Eagle(s), occasionally visible in off-shore stands of trees, were not in evidence. There was nary a trace of the vulture flock(s), of which I have been quixotically fond ever since they lured me to the Sanctuary area in the first place. Small fish, which had been manically breaching and skipping around like stones in the open water only 3 days previously, had evidently retreated to the “depths”. The mosquitoes and gnats were also pleasingly sparse, a trade-off that eased my sense of the Sanctuary's austerity only slightly.

Even the plant kingdom offered diminishing visual rewards, as the goldenrod, jewelweed, pokeweed, skunk cabbage, assorted asters, water lilies, etc. were at varying stages of decay. The Sanctuary's deciduous trees epitomized the relatively feeble 2017 leaf color season: oaks were as drab as ever, nut and fruit trees seemed barely touched by Fall, and even maples and sumacs registered only stray patches of red or orange.

As a fisherman on the jetty gave up after multiple fruitless casts and packed up his gear, I fell into rumination about the many species I'd not seen or seen only fleetingly this Spring, Summer and early Fall (“my bad”, in that I visited the Sanctuary only 2-3 times weekly in the now-waning 017 warm season, versus more like 5 times per week in my introductory 2016 season). I was getting ready to follow the fisherman up to the street when, WAIT, WHAT WAS THAT DARK SEEMINGLY MOBILE SPECK IN THE RIVER FAR TO THE WEST? I trained my binoculars on the area, expecting to be disillusioned, given the tendency for the many exposed stumps, branches, debris accumulations and tiny islets to project an illusion of animal life when shifting water levels and play of light outline some suggestive contour.

This time, though, I found I was watching a brown or black mammal recurrently dive under the water and then emerge head-first. With size and detailed features impossible to visualize at the distance, I wondered whether this was a resident beaver or a an unusually large muskrat or mink. Then the animal began to make its way casually through the water in my general direction. Its movement didn't resemble a beaver's business-like V-waked linear progress. Instead it meandered, wandering off on tangents as it gradually came closer (not that it wasn't capable of impressive swimming speed as it revealed in occasional short bursts).

The tangents afforded profile views of its swimming style, which was entertainingly suggestive of a sea serpent, a would-be Loch Ness monster, or a dolphin lacking a dorsal fin. The head would surface, then dip under, as the animal's sleek, relatively elongated brown back replaced the head above the surface, a sequence repeated with a decidedly sinuous and somehow playful aspect. As it came into closer visual range, its sleek dark head projected a canine outline with an impressively whiskered snout. Only 3 possible identities now remained, all appealing, even exciting. In truth only one possibility was even remotely realistic: I was almost certainly being entertained by an otter. The word “entertained” is specifically apropos, in that the creature's effortless aquatic navigation was a joy to watch, even without a slick creek bank for it to slide down, or underwater views possible in a zoo's glass-encased otter exhibit.

The otter stopped advancing perhaps two hundred, feet from my vantage point on the jetty. For a good ten minutes it puttered lazily around, occasionally performing beautifully rapid and compact surface dives punctuated by a lightning-fast last-second flip of a slender pointy tail, which then disappeared, completing the dive. The dives generally lasted 10 to 15 seconds unlike beavers, who often stay down for minutes, occasionally for ten minutes or more.

Then the otter dove and didn't come back into view in ten or fifteen seconds, nor in a minute nor two nor three. If it had surfaced at all, it might have been in a place hidden by one of several tiny islets a good hundred yards to the north in front of a longish west-east island that borders the main West River channel more or less opposite the Marina Restaurant, but I couldn't seem to spot it there.

Already thankful for the show I'd seen (I'm not life list-driven, but would have been proud to log this sighting) I turned south for one last peek at the Retreat pond before departing. Lo and behold, perched on a snag in the middle of the pond was a Double-Crested Cormorant, the first I'd seen in several weeks. Unlike Cormorants previously sighted in the area, this one was in the cruciform pose that I have come to expect of resting Cormorants: its wings (whose feathers are not waterproofed by oil) stretched out horizontally to speed feather drying. A more-than welcome last-gasp coda to a suddenly memorable Sanctuary visit.

Looking back from the midpoint of the trail to Eaton Ave, I spied the tell-tale dark head, now little more than a speck, in a short, narrow channel between an islet and the barrier island. The Otter seemed to have gone into a diving frenzy: down for 10 seconds or so, then up for a quick breath, then back down again. Had it found a school of tasty fish for lunch? From the distance I couldn't tell whether it was gulping down scaly or shelled prey. Given the exceedingly shallow waters around the fringes of the islands it seemed remarkable that the otter could even manage to fully submerge its body. Certainly the Sanctuary waters provided scant scope for the Otter or the Cormorant to exercise formidable diving capabilities, but then why turn down an easy lunch?

And yes, the chipmunks were still at it; they razzed me mercilessly as I trudged uphill to the head of the Sanctuary trail. Bless the feisty little buggers, I wouldn't have it any other way.

Nighthawks

Winged bug zappers of the Goatsucker persuasion help usher in the Fall migratory season while throwing a scare into Hogle Sanctuary's insects.

I've continued to visit the Sanctuary semi-regularly since that posting, dashing off copious field notes about sightings, but not managing to file completed stories. The reasons for my siege of writer's block fall under the dreary umbrella of life-stage challenges, residential move-associated fatigue and old fashioned neurotic procrastination. I offer a crestfallen “mea culpa” and the assurance that my love of subject matter and desire to share experiences with you have not waned in the least.

I'm writing now in response to an unexpected and highly evocative Labor Day weekend aerial visitation by a squadron of Common (so-called) Nighthawks. For an all-too brief span of days these endearingly zany winged acrobats staged dusk air shows over Hogle Sanctuary's waters and the Eaton Ave/Putney RD corridor. Beyond entertainment value, the nighthawk visit was also a probable harbinger of the Fall migratory season, and it brought my urban naturalist past (in which nighthawks galore plied their trade around the city medical centers where I plied mine) into register with my recent focus on the less megalopolitan (sic) environs of Hogle Sanctuary.

Common Nighthawks are members of a tenuously owl-related family, Caprinomulgidae, also including Whip-poor-wills, Poor-wills, Chuck-will's-widows and others. They are partially to fully nocturnal and voraciously insectivorous. Given their nocturnal habits, eerily verbal calls, erratic flight patterns etc.,. they have, perhaps inevitably, become prime subjects of folklore and superstition. A myth going back to Aristotle or before gave rise to the family's colloquial name, “Goatsuckers”. I'll leave it to the Roman natural scholar-philosopher Pliny the Elder as quoted by our era's premier bird expert, David Sibley, to explain how this name came into being:

“The Caprimulgi (so called of milking goats) are like the bigger kind of Owsels [Thrush]. They bee night-theeves; for all the day long they see not. Their manner is to come into the sheepeheards coats and goat-pens, and to the goats udders presently they goe, and suck the milke at their teats. And looke what udder is so milked, it giveth no more milke, but misliketh and falleth away afterwards, and the goats become blind withall”. (77 AD, from a 1601 translation)

While the specter of milk-deprived and blinded livestock no longer inspires fear in herders, the Caprinomulgidae retain a powerful grip on the human imagination. In my own case, for example, I have never actually seen a Whip-poor-will (nor most other Goatsuckers, given their expertise in hiding during daylight), but I'll always remember the hair-raising emotional impact of the only Whip-poor-will call I've ever heard. Those three syllables, eerily human sounding, stood out with mournful clarity over the 1 AM hush of what later proved to have been a sadly portentious night. Superstition indeed.

While nighthawks emit entertaining (rather than somber) vocalizations {and males produce impressive sonic-boom like whooshing effects via steep dives in the throes of courtship}, they are distinctive largely for their attention-arresting aerial hijinks. Unlike most other goatsuckers, and in contradiction to their name, nighthawks are not exclusively nocturnal, but rather “crepuscular”, ie, most active during dawn and dusk hours when they are at least somewhat visible to humans. To compound the misnomer, nighthawks are not related to true hawks, despite having elegantly slim, tapered, kestrel-like wings with a kestrel/merlin-like 2-foot span. (I 'd also argue that there's nothing “Common” about any nighthawk but the name does have a decided ring to it)

Nighthawks' individual wingbeats are beautifully clean, and the birds are adept at hover-and-plunge maneuvers like those of kestrels, kingfishers or terns, but it is their their erratic flight paths that truly set them apart. Rarely do they fly more than 2 or 3 beats in a single direction; instead they veer and twist horizontally and vertically in seemingly antic manner, often with brief glides denoting direction changes. They move through altitudes ranging from backyard tree house level to hundreds of feet aloft in groups attracted by densities of flying insects, but display none of the cohesive flight dynamics of, say, blackbird flocks. Bright moonlight and artificial light, often present during hunting forays, illuminate prominent white wing blazes, such that peering upward through a nighthawk hunting party can be dazzling and even kaleidoscopically dizzying. During their aerial foraging, nighthawks emit buzzy monosyllabic croaks referred to as “peeent calls”every few seconds, adding an audible kick.

Though often referred to as moth-like or bat-like, nighthawk flight in its apparent madness is highly purposeful, and wondrously effective as a method of plucking flying insects out of the air, when coupled with the species' wide gape capacities and with the helpful prey-funneling effect of abundant facial bristles (both enhancing bug catching capacity of small beaks), and large and keen dusk-adapted eyes. Stomachs of Common Nighthawks felled in mid – hunt have been found to contain 500 or more mosquitoes or 2000 flying ants as well as flies, moths, beetles etc. {Perhaps “tropospheric vermin vacuums” is more apt than “aerial bug zappers” (above)}. I like to entertain the idea, probably just a fond fantasy, that every “peeent” heralds the removal of a bloodsucking potential West Nile/Zika/Malaria vector from the local biome.

As a world class mosquito magnet, long resigned to itchy consequences of warm weather outings, I view Nighthawks' prodigious insect consumption as one of their most endearing features, and I wish that they were an established local breeding population or at least a significant resident presence. In fact Brattleboro, with its buggy meadowlands, waterways and marshes flanking the Hogle-proximal Putney Road corridor, and its many theoretically suitable nesting sites in the form of flat roofed commercial and utilitarian buildings would appear to be a promising Nighthawk breeding area. Moreover, a seeming (to me) decrease in numbers of local swifts and other diurnal insectivores this past summer, together with an unusual abundance of standing water could have led to an enriched local prey population.

Alas, in my experience nighthawks are at best occasionals in the Brattleboro area. During 7 Vermont years prior to this Labor Day weekend , I had seen exactly one Nighthawk- on a warm day some 3 to 4 years ago swooping across Canal Street in the Burger King/Irving Station area as I was heading north from Exit 1. This all-too-brief sighting excited me to a borderline hazardous degree (I pulled off, before I could crash the car) but the bird quickly disappeared. Still, that momentary teaser reminded me how much I miss the flocks of Nighthawks that used to congregate over the parking garages and hospital buildings of Med Centers that once employed me. It is, of course, entirely possible that there are legions of Common Nighthawks nesting around greater Brattleboro, and that I have just missed them, but other trusted observers tend to reinforce my impression that the local area hosts few if any breeding nighthawks.

All of which brings us to the eve of Labor Day weekend '017. I was driving East on Western Ave/High St around 6 PM Thurs Aug 30, when I saw a pair of nighthawks swooping above the park by the corner with Union. With no opportunity for a safe stop, I mentally filed the viewing as probably my only nighthawk encounter for the 2015-2020 time span and moved on. Around 7:15, my appointment over, I headed north on Putney RD, and suddenly found myself driving under an aerial Nighthawk family reunion as I approached and crossed the West River bridge and headed for the Sunoco station. Nighthawks were reliably on hand, not in massive numbers, but 2 or 3 flashed past my windshield every hundred feet or so, enough to hold my attention.

Heading south after the fill-up I pulled off Putney onto Eaton Ave and parked near the Hogle sanctuary entrance as a gaudy late sunset gave way to afterglow. As I got out of the car a couple of low-flying nighthawks careened past – appearing and vanishing among the ̴ 50 foot maples and oaks and taller pines in surrounding yards. Then came a single bird, then a trio, and so on. I tried out my binoculars long enough to establish the futility of that experiment, then decided I had to check for nighthawk action at the Sanctuary's water-level vantage point.

By now the western horizon was graying out, and the entire viewing area had taken on a progressively dimming noire-ish black white and gray character, but nighthawks were still faintly discernible working their magic in the distance near the West River's north shore: not battalions or platoons, perhaps a dozen or so. This entire evening episode was nothing like blow-out Goatsucker air shows I recalled witnessing evenings above the upper deck of Cincinnati Childrens' parking garages. There, bright institutional lighting often captured Escher-like scenes in which nighthawks swirled from just overhead to so far up that they appeared to be scarcely more than dot size. Still, the evening's encounter was a welcome experience (and given that my most recent previous visits to the Sanctuary area were during broad daylight, it is entirely possible that my sightings were just the latter stages of a more copious local pass-through).

Comparing notes with expert sources, I learned that Vernon had also just had a transient nighthawk visitation, but that there was not much hope that local stopovers would last long. This pessimism was confirmed: I saw only one grouping of 3 nighthawks above the West River delta area on Sat Sept 1, and none on subsequent evenings, although a spectacular full moon glimpsed low over Mt Wantasquitet made a nighthawk-less Sunday Sept 2 outing worthwhile.

The literature provides a clear rationale for the brevity of what was presumably an early-migration stopover: Common Nighthawks make a long migratory journey, eventually crossing the Gulf of Mexico en route to winter territories in sub-equatorial South America and leaving them little time for early stage loafing around. Thus, though subsequent itchy welts on my hands and ankles attest to the continued abundance of mosquitoes in the Hogle area, I'm grateful that the nighthawks hung around long enough to gobble up SOME bugs, while gifting me with a night's entertainment. As the merchants of Durham NC (above which the migrating nighthawks might indeed pass) were wont to say to customers during my 1970's stint as a Duke grad student, I say to the southbound nighthawks: “Y'all come and see us agin sometime, y'hear?”

The Sanctuary in Late Winter:

a Long-Deferred Visit to Hogle Offers Rewards and Raises Concerns

— part 2 —

The visit was more than worth the effort, though, as signs of life had again become abundant against a dramatically altered scenic backdrop. The snow surrounding the upper trail and descending risers was pocked with animal tracks, most of them indistinct due to wear and attrition, but at least some clearly from creatures other than the many family dogs that take their constitutionals at Hogle. When the boardwalk area and the sweep of the water came into view effects of snow melt were eye-popping. Water that had spilled over from the lagoon -like south shore of the West River, created a canal of sorts under the boardwalk. Waters around the narrow connecting channel between what I think of as distinct Retreat pond and predominantly West River waters, were only partially frozen over as opposed to the near-hermetic icing of a few short weeks ago.

The channel itself, normally fairly placid, was flowing north from pond to River at a good walking pace, as illustrated by movement of detached pieces of ice and other flotsam. The water itself was roiled, with standing waves and small shifting whirlpools radiating from rocks, cement and other solid features on the banks and below the surface. The water level was the highest I'd personally seen: standing on the North – facing jetty, I was less than a foot above the water surface, and an a nearby tangle of iron spikes set in sub-surface cement was totally submerged for the first time in my experience.

The return of active wildlife to the Sanctuary was low-key but heartening. Small junco-like birds and paisley sparrow-like birds darted back and forth between the boardwalk area and clumped trees across a meadow area, too fidgety and elusive for any firm IDs, Redwings were heard but (strangely) not seen, geese were back (of course), gulls (virtually absent during warm months,) wheeled and squealed around the ice fishing area, probably angling for bait or thieve-able catches. A small gaggle of spiffy ducks – with bold black and white patterning and large all-dark flat-topped heads, (Ring necked Ducks? Golden Eyes? Scaups?

Leaving around 4 PM as it began to drizzle, I made a last binocular sweep and saw that a bedraggled and jaded -looking Bald Eagle had perched on a tall deciduous tree on the strip of land projecting from the cement hulk. Too far away to see much except a bedraggled and vaguely disgruntled look. The perch location was very close to that for a previous Eagle spotting 2- plus months ago (habitual command post?).

I close this installment with a note of concern. Berkeley Veller "For Sale" signs that had gone up in the Fall on a mostly level bluff -top near the upper Sanctuary trail, with a commanding view of the Marina (location, location, location) had disappeared, possibly signifying that development is just around the corner. The hope here is that calendar Spring will not bring with it any of the quaint “Thickly Settled” signs that mark the approach to Brattleboro subdivisions such as the nearby neighborhood between Cedar and Spruce Streets.

The Sanctuary in Late Winter:

a Long-Deferred Visit to Hogle Offers Rewards and Raises Concerns

— part 1 —

Some of you may recall my Summer and Fall '016 pieces extolling the Hogle Wildlife Sanctuary, an aesthetic and naturalistically eventful location overlooking the convergence of the Brattleboro Retreat Meadows with the West River Delta, and commanding views of Retreat buildings, Ski Slope, Grafton Cheese, Marina and Black Mountain among other local landmarks.

In a Fall piece I ruefully chronicled the departures of the warm weather regulars, while noting compensatory pre-migratory and migratory visits that enlivened this transitional period. Among these were a week-long stopover by four Double Crested Cormorants, a seeming family group including a probable first year “apprentice” refining his/her diving skills, day by day, and a Harrier (aka “Marsh Hawk”) couple seen daily for almost a week as they wheeled and veered and screeched just above the cattails and wildflowers of nearby islands-terrorizing resident rodents. In addition flocks of migratory Flickers, Waxwings, Goldfinches, Hummingbirds and assorted sparrow and warbler-sized squeak-birds dropped in to fatten up on Jewelweed nectar, choke cherries, acorns, and weed seeds in preparation for arduous south-bound journeys. In addition I had brief glimpses of a Pileated Woodpecker, a Black-Crowned Night Heron and a stoical-appearing Bald Eagle who favored a perch high in one of a cluster of barren tall deciduous trees near the cement hulk. Numerous small fish staged daily exhibitions of skipped stone-like leaping. Needless to say, gaggles, nay, HORDES of Canada Geese staged their Fall onslaught, adding a noxious blend of cacophony, floating pinfeather lint, and fecal pollution to the scene. (Dickensian England may have had a point: besieged waterways and park-lands might benefit if more geese [at least our over-successful Canadian strain]were to be found on dinner tables instead of all over prime habitats, but hush my mouth, I'm a declared crank on this point).

As November wore on, even such enlivening animal drop-ins came to an end. Meanwhile, the Sanctuary grounds crew, wisely, I'm sure, yet depressingly razed the area's dense cover of withered wildflower stalks and weeds down to stubble, much of the open water froze over, and the snows came. The result was still-beautiful, but bleak austerity, with even the year-around crows, jays and small back yard feeder birds maintaining curiously low profiles.

I confess that visits to Hogle in full winter became a struggle for me. I'm intrigued by winter's bustling sub-nivean wonder-world of tunneled-in rodents, shrews, arthropods and small birds, and I'm vastly impressed by mind-boggling strategies that enable tiny creatures like Kinglets to survive frigid nights that should, common sensically, reduce them to 0.21 ounce ( meaning 4 or more Kinglets could be mailed with a single first class stamp), birdsicles.

As fascinated as I am in principle by these subtle marvels, however, they don't satisfy my craving for more readily observed animal doings, nor or counteract my inner wimp as it relates to cold snaps, howling winds and treacherous footing. Thus I took a break of over a month from the Sanctuary, during which I worked sporadically on “Hot Stove” pieces about crows' colorful and sometimes melodic exploits and avian flight styles, leaving a trail of manuscript scraps that I hope to mine some day.

It was not until mid-afternoon Sat. February 25, after my return from 4 days in MD, (where there was no trace of snow even in the Blue Ridge foothills, temperatures reached 70- 75 degrees every afternoon and spring harbingers were everywhere), that I ventured back to the still snow-encrusted trail leading down from Eaton Place to the Sanctuary observation point. The approach was somewhat challenging, as the most direct and hence most trodden center part of the trail was packed down to ice and slick-wet given the 50 degree temperature, necessitating circuitous descent through the less compacted surrounding snow.

Hogle in Fall:

a Subdued Sanctuary Hunkers Down for Winter

The Hogle Sanctuary, whose exuberant warm weather charms I praised in Vermont Views a couple of months ago, has presented a more subdued facade of late. Most deciduous trees have been barren for a month now. Even Maple saplings that had remained green for weeks in the shadows of their largely denuded parent trees at the Eaton Place end of the Sanctuary trail, started yellowing as October kicked over into November. By now they, too, have contributed most of their leaves to the dense underfoot mat. Factor in the still depressing (to me) stunted appearance of the Sanctuary acres south of the boardwalk, where the once lush mix of wildflowers, tall grass and plain weeds has been so closely cropped down by Foundation groundskeepers as to invite scalping analogies, and the composite visual effect is stark, austere; impressive in its severity, but not my style.

Starting in early October, a series of presumed migratory stop-offs by non-resident birds has provided a partial antidote to the Sanctuary's Fall doldrums: a flocklet of Flickers one day; then a squadron of Hummingbirds strafing remaining Jewelweed blossoms; a day of Cedar Waxwings; a week-long fishing exhibition by 3 double crested cormorants (2 adults and one youngster, who displayed impressive day-to-day progress in sub-aquatic pursuit of prey fish); a hugely entertaining appearance by a pair-O -Harriers (aka Marsh Hawks) whose wheeling, veering low-down (barely above the tall grass) hunting flights were aerial counterparts to broken field carries of legendary NFL running backs like Gayle Sayers, Barry Sanders and Eric Dickerson (Yes, alas, I'm that old, I even remember seeing the great Jim Brown play).

These visits, and occasional fly-overs, for example by two Bald Eagles (not quite together, but in fairly close succession- a pair?), by a Kestrel-sized falcon in seeming pursuit of a Merlin-sized falcon, a forest canopy flight by a large accipiter (a Goshawk?) helped me to cling to residual enthusiasm for visit after visit. Then, as early November swirled miasmically down the drain courtesy of the Election Day/ Black Wednesday maelstrom, these compensatory avian sideshows came to an end.

Suddenly there was near-silence, broken only by the occasional utterances of suburban-style bird feeder regulars: Chickadees, Nuthatches, Juncos, Crows, Jays. There was, of course, the honking of Canada Geese in flotillas or in overhead vees. Worse than the diminished avian chatter was visual stasis often so profound that virtually every detected flash of motion proved to be the final descent of some stubbornly adherent leaf that had finally given up the ghost.

Up to a point I appreciate somber still-life vistas, but for the most part my huge appreciation for the Sanctuary resides in the opportunities it can provide to witness creatures plying their trades with creature-esque skill, diligence and elan: hunting, fishing, mobbing, defending territories, rebuffing intruders, and sometimes apparently just plain frolicking around. Minus this inducement, my frequency of Sanctuary visits has gradually decreased from 5 or so to 2 or so per week, AND I almost turned down an opportunity to visit the Sanctuary this afternoon (Sunday Nov 27). Silly me.

Fortunately I DID drag myself lethargically to the Eaton Place Sanctuary entrance, thence down from the trail head (and past recently erected realty signs ominously advertising the availability for sale of a prime trio of house lots just off the Sanctuary trail opposite the Marina), and on down the boardwalk. The silence was deafening at the upper end of this descent, only slightly leavened by a solitary chickadee. The waters around the concrete jetty seemed atypically barren. None of the small fish I'd often seen leaping about were in evidence this afternoon, nor were any fish, large or small, visible in the shallows around the jetty. In a marked departure from normalcy, there was no response to bits of Putney Road fast food Fries, which floated undisturbed when flipped into waters that usually harbored hungry fingerlings.

Resigned to an unrewarding visit, I started back toward the boardwalk and my car, in the process casting one last glance toward an area in the Retreat Pond, slightly south of, and perhaps 100 yards west of the pumping station. I'd noticed occasional surface disturbances there, but had scant hope that any resident muskrat, beaver or mink was responsible for them, not having seen any of these species for months. Then, suddenly, a dark head and a trailing V-shaped wake emerged.

This was my first sighting of any beaver from the local colony's nearby lodge since August. It threatened to be a brief sighting, as the wary beast executed a crisp, clean, compact surface dive the moment I tried to train field glasses on it, and rapidly disappeared from view. The dive was not a prelude to flight of the agitated tail slap variety, however; rather the beaver resurfaced after an estimated minute or so. This time it rode sufficiently high in the water to partially expose head, body and tail segments to a degree that made them appear to be barely connected, making the body- to- tail junctional region vaguely resemble a broad piece of ribbon twisted and rounded into 2 segments. The Beaver seemed to be repeatedly criss-crossing a circumscribed area for reasons that never became obvious to me. It made 3 more dives while I watched, coming up the last time (one hopes it came up) somewhere out of my view.

One of the dives led to an apparent 3 minutes or more of immersion. With the caveat that the Beaver could easily have pulled a fast one on me and surfaced unseen to sneak a breath during that period, I would like to think that it truly did manage an impressive 3 minute breath hold. The actual likelihood of such a feat of oxygen husbandry is probably a known entity: something to look up during one of late Fall's dank and dreary evenings.

Meanwhile I'd been treated to an intriguing display of the aquatic capabilities of a crafty rodent, and had, at the same time, been issued a reminder that, as the Holiday Season thunders upon us, the Hogle Sanctuary might just be a gift that, like the Christmas of song, keeps giving the whole year around.

The Hogle Panorama

Part 1

An opening disclaimer: I seem to have subconsciously arrived at a title in the stylistic mode of famed crime and espionage novelist Robert Ludlum (eg: The Bourne Identity, The Hogle Panorama). This choice was not meant to reflect a personal stance versus Ludlum's literary footprint; about which I am essentially neutral..

This piece is about my awakening to a naturalistic and aesthetic Brattleboro treasure nestled in the bluffs and hillsides that ring the south and east shores of Retreat Meadows Pond, a venue probably known to many of you: the John R. and Grace D. Hogle Wildlife Sanctuary. I'll relate how 2 unlikely emissaries: a bird of an often feared and reviled species, and a furry garden pest, lured me into 'Hogle Country', and triggered some 50 visits to one very special vantage point that displays in a condensed manner a great deal of what the Sanctuary has to offer. In this and future installments I'll touch on the varied habitats and wildlife that I've seen in action there as Spring morphed into Summer and Summer wore on, and will describe one prolific July afternoon's creature encounters. More such Hogle snapshots will follow in future installments.

I was walking along Putney RD just south of Bradley Ave early on a brisk April ('015) Sunday, when a flash of motion overhead caught my eye- a large soaring bird. It turned out to be a vulture rather than one of the rarer and arguably “sexier” Bald Eagles that occasionally cruise this air space, but I continued to track its flight, having developed an interest in Brattleboro's peripatetic band of vultures The obvious “yuck” factor aside, I can't help admiring these imposing birds' mastery of air currents; the supreme ease with which they deploy 6 foot wingspans, capturing updrafts which propel their bulky 4-5 lb bodies to commanding heights. In subgroups they ride aerial circuits like saturnine itinerant preachers, collectively seeing more of what transpires (or has expired) in this SE corner of VT than any other local creatures. I have imagined the flock as the avian Greek Chorus that the self- professedly unique town of Brattleboro must certainly merit. *.

My interest intensified when the vulture coasted west and south toward the Retreat and banked smoothly down into a Logan Airport-style over-water landing into a “vulture tree” or “buzzard bush” on the Pond's south shore at the base of bluffs supporting a row of Retreat buildings. This tree was festooned, or decorated (depending on your sensibilities) with 15- 20 of the massive birds, all starkly visible, on the tree's as yet leafless branches.

I was shocked to see vultures still in the tree when I returned to my parking place an hour later. I decided to take this virtually unheard-of breach of Murphy's Law of Animal Perversity as an omen and an invitation. I drove to the Retreat's northern-most lot and walked past pool and maintenance sheds to the nearest overlook point. In another violation of Murphy's Law, the vulture tree, still weightily occupied (or as road signs sometimes quaintly say of local neighborhoods: “thickly settled”), was immediately visible. Walking a sloping path down to a basically level west-bound shore trail, I approached the tree closely enough (within 50 feet) to get a visceral sense of the sheer size and power of the vultures, as they coasted in and out one by one. At close range the sight was ominously reminiscent of a Tim Burton creation I once saw at a Disneyland Haunted House: a perversion of the traditional American living room during Christmas season featuring a tree lavishly decorated with skulls, vampires, maniacal Jack-O-Lanterns, and other ghoulish Halloween items.

The vultures paid little attention to me (sensibly, in that I was neither a credible threat, nor [quite yet] a prospective entree for Sunday brunch). I speculated that this and/or neighboring trees might serve as regular nightly roost(s) for the flock. Finding such a communal roost would have been a valuable aid to an inquiry I've been fiddling with, that relates to dynamics, causes and implications of the past few years' northward extension of the range of Black Vultures, a southern interloper species now infiltrating SoVT's pre-existing Turkey Vulture population. Future visits didn't support the regular communal roost hypothesis. In fact it seems likely that the Sunday AM vulture congregation I'd happened on was there in response to a contemporaneous fish kill, as my nose and eyes led me to 4 large fish carcasses bobbing in nearby shallows, emitting a stench potent enough to mask the the vultures' own aroma.

This account of what are, after all, ugly, gross, disquieting stinky birds and stinkier fish may seem like bait-and-switch after a lead-in about “a natural and aesthetic treasure”, (Did you know, BTW, that vultures' lack of head feathers is believed to be an adaptation making it easier to root around INSIDE carcasses? All together now, Yeccccchhhhh ! Or as some flight hostess might say: “Stash your carrion in the overhead bins and keep those white paper bags within easy reach” ), but not so.

The Hogle Panorama

Part 2

The (unmarked) trail that brought me to the vulture tree was, unbeknownst to me, the southwest “lobe” of Hogle Wildlife Sanctuary. Running west along the densely thicketed Retreat Pond shore to the kayak/canoe launching area opposite the Retreat Farm, it offers an assortment of natural encounters (sassy catbirds and wrens, cardinals, doves, Goldfinches, confusing sparrows warblers and flycatchers Chickadees and other feeder birds, fish, crustaceans, discarded remnants of machines and outbuildings from earlier Retreat eras, numerous effluent pipes, and, as counterpoint to such gritty items, picturesque across the-water views of mountains, hills, the Farm and Marina areas, the glacial progress of the I91 West River Bridge project, etc.

After multiple visits to this trail, a furry miscreant took me in hand (in paw?) in early May '016,and steered me to what the late syndicated radio raconteur Paul Harvey might have called “The rest of Hogle”. I was passing by the Retreat pool when I nearly collided with a gigantic groundhog emerging from beneath a maintenance shed-or the adjacent port-a potty (near a Retreat garden patch, of course). The hefty gopher scuttled east/northeast with me in pursuit- bringing us to the north edge of a playing field, AND to the unmarked head of what I would soon learn was the other main segment of Hogle Sanctuary trail. Turning north, this trail hugs cliffs beneath Putney Road's B and B's** and prosperous homes, meandering up and down for perhaps half a mile through deciduous and evergreen woods, crossing gullies on wooden bridges, skirting logs and boulders and spinning off rustic tangential paths en route to a remarkable northern terminus. It provides a genuine feeling of seclusion, remarkable considering the proximity of bustling Putney/Rte5. Its ups and downs and rockier terrain make it a more challenging hike than the western leg, though I've met fitness mavens jog its length as part of aerobic workouts. It has provided my only other “vulture tree” sighting in the Retreat Pond area – right by one of the wooden bridges- but this and the woodchuck have been my main creature encounters during several spring and early summer traversals. The density of foliage screens out much overhead bird life and partially obscures views of the Pond and surrounding scenery, that is, until the trail reaches its remarkable northern end.

As the northbound hike nears the West River Delta/Marina area, it emerges from woods into a relatively flat zone, a meadow run to riot: lushly overgrown (my experience being exclusively in spring and summer so far) with vines, berry bushes, shrubs, saplings, milkweed, pokeweed, goldenrod, skunk cabbage, burdock, thistles, ragweed, lambs quarters (?), lavender and other hearty “warrior weeds” forming dense tangled shoulder- height overgrowth of near-impenetrability except where criss-crossed by several Hogle Foundation- maintained trails. Toward the north and west end of this meadow zone is a small relatively cleared out tree- dotted “head” a natural observation deck that's a magnet for visitors of all sorts. A table with a bucolic VT farm scene painted on its circular top (decorative albeit somewhat trumped by water-enhanced wraparound (yes, panoramic) views of actual surroundings: the Retreat, Retreat Farm, Black Mountain, the Marina, the stone turret and other curious structures nested in the hills) sits next to a stone bench above a fairly steep bank leading down to a narrow channel that is a favored kayakers' and canoers' passage between the Retreat Meadows Pond and the West River Delta/Marina area. Across this channel is a massive abandoned concrete structure vaguely resembling a gigantic open-topped railroad freight car compartmentalized by 7 or 8 concrete cross bars, beyond which to the north are additional vertebrae-like “naked” concrete slabs, some above water, others shallowly submerged. The net effect is vaguely evocative of Roman ruins in England's Cotswolds. Rich Holschuh, an expert on regional cultural history (and the person who first informed me that I had been obliviously blundering around in the Hogle Sanctuary) revealed that the concrete artifacts are relics from an archival attempt (unsuccessful) to pump water out of what is now the Pond and maintain it as dry land. Naturalistically speaking these structures with their ledges and nooks and crannies provide the types of hiding places that attract fish, and there is a beaver lodge hidden to the west along the shore of a skinny barrier island that the massive concrete structure adjoins.

The Hogle Panorama

Part 3

The (unmarked) trail that brought me to the vulture tree was, unbeknownst to me, the southwest “lobe” of Hogle Wildlife Sanctuary. Running west along the densely thicketed Retreat Pond shore to the kayak/canoe launching area opposite the Retreat Farm, it offers an assortment of natural encounters (sassy catbirds and wrens, cardinals, doves, Goldfinches, confusing sparrows warblers and flycatchers Chickadees and other feeder birds, fish, crustaceans, discarded remnants of machines and outbuildings from earlier Retreat eras, numerous effluent pipes, and, as counterpoint to such gritty items, picturesque across the-water views of mountains, hills, the Farm and Marina areas, the glacial progress of the I91 West River Bridge project, etc.

After multiple visits to this trail, a furry miscreant took me in hand (in paw?) in early May '016,and steered me to what the late syndicated radio raconteur Paul Harvey might have called “The rest of Hogle”. I was passing by the Retreat pool when I nearly collided with a gigantic groundhog emerging from beneath a maintenance shed-or the adjacent port-a potty (near a Retreat garden patch, of course). The hefty gopher scuttled east/northeast with me in pursuit- bringing us to the north edge of a playing field, AND to the unmarked head of what I would soon learn was the other main segment of Hogle Sanctuary trail. Turning north, this trail hugs cliffs beneath Putney Road's B and B's** and prosperous homes, meandering up and down for perhaps half a mile through deciduous and evergreen woods, crossing gullies on wooden bridges, skirting logs and boulders and spinning off rustic tangential paths en route to a remarkable northern terminus. It provides a genuine feeling of seclusion, remarkable considering the proximity of bustling Putney/Rte5. Its ups and downs and rockier terrain make it a more challenging hike than the western leg, though I've met fitness mavens jog its length as part of aerobic workouts. It has provided my only other “vulture tree” sighting in the Retreat Pond area – right by one of the wooden bridges- but this and the woodchuck have been my main creature encounters during several spring and early summer traversals. The density of foliage screens out much overhead bird life and partially obscures views of the Pond and surrounding scenery, that is, until the trail reaches its remarkable northern end.

As the northbound hike nears the West River Delta/Marina area, it emerges from woods into a relatively flat zone, a meadow run to riot: lushly overgrown (my experience being exclusively in spring and summer so far) with vines, berry bushes, shrubs, saplings, milkweed, pokeweed, goldenrod, skunk cabbage, burdock, thistles, ragweed, lambs quarters (?), lavender and other hearty “warrior weeds” forming dense tangled shoulder- height overgrowth of near-impenetrability except where criss-crossed by several Hogle Foundation- maintained trails. Toward the north and west end of this meadow zone is a small relatively cleared out tree- dotted “head” a natural observation deck that's a magnet for visitors of all sorts. A table with a bucolic VT farm scene painted on its circular top (decorative albeit somewhat trumped by water-enhanced wraparound (yes, panoramic) views of actual surroundings: the Retreat, Retreat Farm, Black Mountain, the Marina, the stone turret and other curious structures nested in the hills) sits next to a stone bench above a fairly steep bank leading down to a narrow channel that is a favored kayakers' and canoers' passage between the Retreat Meadows Pond and the West River Delta/Marina area. Across this channel is a massive abandoned concrete structure vaguely resembling a gigantic open-topped railroad freight car compartmentalized by 7 or 8 concrete cross bars, beyond which to the north are additional vertebrae-like “naked” concrete slabs, some above water, others shallowly submerged. The net effect is vaguely evocative of Roman ruins in England's Cotswolds. Rich Holschuh, an expert on regional cultural history (and the person who first informed me that I had been obliviously blundering around in the Hogle Sanctuary) revealed that the concrete artifacts are relics from an archival attempt (unsuccessful) to pump water out of what is now the Pond and maintain it as dry land. Naturalistically speaking these structures with their ledges and nooks and crannies provide the types of hiding places that attract fish, and there is a beaver lodge hidden to the west along the shore of a skinny barrier island that the massive concrete structure adjoins.

Meanwhile the Pond in its un-drained glory adds to the acreage and diversity*** of the Sanctuary's water habitats also including various channels and backwaters of the West River, the CT River and ultimately the Long Island Sound (lamprey, anyone?) . These waters and a meshwork of islands are home to Great Blues and sometimes other herons and wading birds, kingfishers, osprey (I'm told), the inevitable Canada Geese, multiple duck species, swallows, Redwing and other Blackbirds, etc and are a flyover zone for Bald Eagles. They also harbor mammals including the aforementioned beaver as well as mink, muskrats, rumored otters and fisher cats and conceivable water shrews; turtles; bullfrogs croaking amid the water lilies and other plant life in the shallows; crustaceans; molluscs and a plethora of fish species. Meanwhile the terrestrial habitats, enriched by the water interface, and by overlap of varied forest types with meadowland, are home to (of course) squirrels, chipmunks and rabbits, as well as field mice, voles, American toads and garter snakes, a large array of resident birds and occasionals, such as flickers and waxwings that visit in waves then are gone. As wildflower species bloom and fade in succession, they attract hummingbirds and multiple butterfly species along with an encouragingly robust battalion of pollinating insects; meanwhile, it must be said, there are also hungry mosquitos**** and, at times, hordes of manically swirling gnats

Last but not least, a plank boardwalk extending from the table and bench area eastward connects to a dirt path ascends bluffs on risers, winds around, and ends at the Putney Road level in a neighborhood (Eaton Place) alongside the one-time Hogle home, at the marked entry point to the Hogle Sanctuary. This path itself a succession of habitats; maple pine, oak and fern zones, the sheltered habitat “Under the Boardwalk”, etc. The shortness (10 min or less) of the walk from this entrance to the table and jetty area has made it possible for me, time-wise, to visit this destination some 40 to 50 times in the past 3 months, essentially whenever I was passing by and could afford a half-hour or so.

I'll close with a description of one of my more captivating visits to the “Hogle destination”. It was early on a mid-July evening. The plant life along the trail had a moist sparkle in the light of the incipiently setting sun and the air felt fresh a few hours after showers and subsequent clearing had provided relief from a hot and muggy week. The gnats were out in force, but the mosquitos were less of a presence than usual. I went to the concrete jetty and noticed that, contrary to expectation, the water level was down relative to the day before (possibly a result of feedback from upstream manipulation of the CT River's flow?) - such that normally submerged areas bordering islands to the north and west were now narrow mud flats. As I swept the area with binoculars, noting that the “usual suspects, a Great Blue Heron and a Kingfisher were “on the job”; then I caught a flash of motion in a small gap in the grass and weed cover on a nearby island. A dark shape emerged from this gap and advanced to the narrow usually submerged mud flat area, showing itself to be perhaps a foot or a foot and a half long, a slender creature sinuous looking like a ferret, blackish in the now-fading sunlight. It proceeded to caper around for several minutes – antic leaps exhibiting a boneless-appearing flexibility. This occurred near a flotilla of brownish ducks which it ignored and was ignored by. I could see no evidence of hunting, rather it appeared offhand that the creature was simply having fun. When it retreated (casually) to its hole in the underbrush I assumed that the show was over, but no, the beast re-emerged a minute or so later and returned to its seeming play on the mudflats. This was the first of several center stage exits followed by curtain calls happening over nearly half an hour before the final curtain came down. BEEC expert Patti Smith later provided support for my hunch that I was describing a mink to her(though it was remotely possible it was a fisher), and field guide sources informed me that the apparent prancing was “bounding”, a form of locomotion involving leaps in which the hind paws land in the former position of the front paws.

Meanwhile I had spotted a wading bird working another small mud flat in another normally underwater zone. Markedly smaller than a Great Blue Heron, but similar tactically, it stalked and froze mime-like inb various uncomfortable appearing positions and gradually worked its way toward the land spit projecting from the massive cement artifact. In the fading light my general impression was of predominant brownness, but the field glasses picked up splashes of russety coloration on a “bib”: a characteristic hue that contributed to my tentative identification of this unaccustomed but welcome visitor as a Green Heron.

Meanwhile I heard a loud splash by the big concrete artifact. As I speculated that a large fish had breached or some beast had leapt a couple of feet into the water from a ledge on the slab, a beaver surfaced, perhaps the one that had previously taken a leisurely swim toward the River's mouth/Marina then approached my post on the Jetty, silently surface dived and disappeared. THIS beaver issued a resounding tail slap (an alarm signal, and what I had just previously heard), dived down and disappeared from view bringing the evening's hour of rapt spectatorship to an end.

Please note, this nature watching bonanza was far from being a typical outing. It has been my only sighting of either mink or Green Herons; truly distinctive sightings are sporadic. Hogle is not, after all , operating on the Disney Animal Kingdom model. It is, however indicative of the kinds of possibilities that this facet of the Sanctuary can offer a frequent visitor.

*My appreciation for Brattleboro's vultures is nothing new: within a year of my Fall '010 arrival in VT I had tipped my hat to the flock in a stanza from a take-off on the Mancini song “Moon River”:

“Moose Crossing”

Now there's a highway sign

That tells you northern woods are nigh.

Where soaring vultures

Define high culture

And Orion hangs touchably low in the sky.

(Thc Greek Chorus concept took a hit when I learned that vultures are severely limited vocally, producing only clicks and croaks.)