Literacy — Part 1, the USA

I have been discussing with some columnists recently who their readers are — and suggesting that the demographic obtained from Facebook is some guide, 80+% of Vermont Views Magazine readers have at least an undergraduate degree.

Here though are the national figures:—

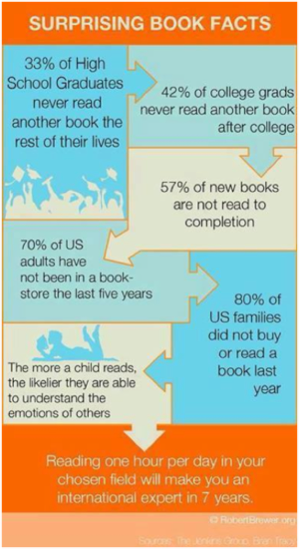

80% of families did not buy or read a book in the past year.

57% of new books are not read to completion.

It is not an exact corollary, but those statistics together indicate that less than 10% of the population read all the way through even one novel in an entire year.

Here are other other statistics about literacy in the USA:—

15% of people have a reading disorder

33% of people never read any book after High School

42% of people do not read any book after they graduate from college.

Hollow and Holy

Halwende. HALWE is A. Sax.: to hallow; to consecrate [by circulatory and kinetic means].

HALWEN; saints.

HALOGHE; a saint or holy one. From MS Coll. Eton 10 f 23 also MS Lincoln A. i. 17 f. 142.

HALEGH, saint, MS. Cott Vespas D vii Ps 14

Gower uses HALLY for Wholly.

HALLE or HALE: well, healthy [A. Sax]

HELE is A. Sax. and I find meanings: to slate, to roof, to cover anything up, but specifically to cover up potatoes, which I remember was in use in my Cornish village. Originally a Devon word, says Halliwell.

HELON: to cover, to hide [Sussex]

Usage is generally in common speech similar to HALANTOW [still celebrated in Cornwall] A procession which used to survey the parish bounds, singing a song with that burden, and accompanied with ceremonies somewhat similar to Furry-day. (In my youth this was called 'Rogation Sunday' by the Methodists who edged away from all this Celtic or Pagan stuff)

There is still a Furry Day celebration in Helston, Cornwall where the citizens dance together and process in and out of the houses in a serpentine route and to a serpentine tune said to be the same one as played in 1200, but the Celtic part of it remembers Romans and Dragons!

Language Translators

I thought I would test on-line language translators based on the American National Anthem, this is what happened after passing the anthem through English to French to Albanian to Cantonese to Arabic to English. I wonder if you agree that the translators are very good indeed, though for vital correspondence perhaps direct language to language expertise is preferable.

O, for example, you can see,

In the light of dawn,

So proudly welcomed

Twinkle last of the twilight,

Stripes and bright stars that wide,

During the war grave,

o'er ramparts we watched,

Even the flow of courage?

And the rockets red glare,

Bombs explode in the air,

The evidence presented during the night

That was our flag was still there.

O, for example, there is a bright banner still waves

In the land of the free

And the home of the brave?

O thus be ever

When the Liberals hold

Between their homes love

And the destruction of the war!

Blessed with victory and peace,

It can land reserved in the sky

Authority lease which has

And preserved us a nation!

Therefore, we will win,

When our cause is right,

And this be our motto,

"We believe in God."

The stars and stripes

In triumph shall wave

In the land of the free

Revenant

A revenant is a visible ghost or animated corpse that is believed to have returned from the grave to terrorize the living. The word revenant is derived from the Latin word reveniens, "returning" (see also the related French verb revenir, meaning "to come back").

Vivid stories of revenants arose in Western Europe (especially Great Britain, and were later carried by Anglo-Norman invaders to Ireland) during the High Middle Ages. Revenants were also known in old Irish Celtic mythology as the neamh mairbh. Though later legend and folklore depict revenants as returning for a specific purpose (e.g., revenge against the deceased's killer), in most Medieval accounts they return to harass their surviving families and neighbours. Revenants share a number of characteristics with folkloric vampires.

Many stories were documented by English historians in the Middle Ages. William of Newburgh wrote in the 1190s, "It would not be easy to believe that the corpses of the dead should sally (I know not by what agency) from their graves, and should wander about to the terror or destruction of the living, and again return to the tomb, which of its own accord spontaneously opened to receive them, did not frequent examples, occurring in our own times, suffice to establish this fact, to the truth of which there is abundant testimony."

Honkie Dilemma

— a derogatory term for a Caucasian person, but which of the following definitions from assorted sources is true?

1. the word originated from the practice of white males wishing to hire African-American prostitutes in the 1920's, and going to the appropriate part of town while honking their car horns to attract the whores. Some versions state that the reason for this was that the white men were too afraid to actually stop in those neighborhoods, so the honking would bring the hookers to them. Others say that since few African-Americans could afford cars back in that time, the honking signaled a higher-paying white client and would quickly gain the prostitutes' attention.

2. the term comes from the word "honky-tonk", which was used as early as 1875 in reference to wild saloons in the Old West. Patrons of such disreputable establishments were referred to as "honkies", not intended as a racial slur but still a disparaging term.

3. "honkie" is a variation of "hunky" and "bohunk", derogatory terms for Hungarian, Bohemian, and Polish immigrant factory workers and hard laborers in the early 1900's. African-Americans began to use the word in reference to all whites regardless of specific nation of origin.

also spelled "honky".

-

4.a double long joint that's rolled by sticking at least two papers together. these resemble blunts in size but instead of being brown they're white hence the name honkie.

-

5.Because whites talk through your nose. Slang for nose is "honker".

-

6.Honky may also derive from the term "xonq nopp" which, in the West African language Wolof, literally means "red-eared person" or "white person". The term may have originated with Wolof-speaking people brought to the U.S.

Attunement

I recently used this unusual word repeating an idea from the philosopher Dane Rudhyar, but I used to live in a community where it was very common. At the Findhorn Foundation in Northern Scotland there was often, even usually, a pause before any activity was begun to ‘tune in’, and hence the adoption of the term. I understand that people have all sorts of practices and orientations to ‘Attunement’ but the Findhorn version was typically more simple — and typically involved an inward facing circle of people about to do something together.

There seemed to be then and now a practical function for this activity and my list below contains several factors to recommend the practice:—

-

a)it is a way to stop whatever had been going on before, or at least make a conscious pause, so that something new could be taken in, without dragging the past with it.

-

b)holding hands is optional in the circle, but physically connecting with others in this way is a foundation activity for other forms of connectivity

-

c)typically someone in the group would ask for a moment of silence, and often this was sufficient — though this ‘focaliser’ of activity might invite the group to consider what they were working with, not just conceptually but as energy forms

-

d) after a moment or two, even just 20 seconds, there seemed to be an appreciable difference in groups attuning to an activity, and to each other, than groups proceeding without this practice

e) which certainly could be incremented to any subsequent organization or process, now that everyone’s attention had been brought to a similar place.

The eye of a needle

Occurring in Judaism, The Koran, Christian and Sufi traditions, each with different interpretations is the phrase "The eye of a needle."

The Christian tradition is from scripture quoting Jesus recorded in the synoptic gospels:—

I tell you the truth, it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. When the disciples heard this, they were greatly astonished and asked, “Who then can be saved?” Jesus looked at them and said, “With man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.” Matthew 19:23-26. Parallel versions appear in Mark 10:24-27, and Luke 18:24-27.

The saying was a response to a young rich man who had asked Jesus what he needed to do in order to inherit eternal life. Jesus replied that he should keep the commandments, to which the man stated he had done. Jesus responded, "If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me." The young man became sad and was unwilling to do this. Jesus then spoke this response, leaving his disciples astonished.

Cyril of Alexandria claimed that "camel" is a Greek misprint; that kamêlos (camel) was a misprint of kamilos, meaning "rope" or "cable". This would make sense or at least a consistent simile, a rope or cable being too wide to thread with a needle.

Have no truck with

Meaning

To reject or to have nothing to do with.

Origin

We are all familiar with trucks as carts and road vehicles, but that's not what's being referred to in 'have no truck with'. This 'truck' is the early French word 'troque', which meant 'an exchange; a barter' and came into Middle English as 'truke'. The first known record of truke is the Vintner's Company Charter in the Anglo-Norman text of the Patent Roll of Edward III, 1364. This relates to a transaction for some wine which was to be done 'by truke, or by exchange'.

So, to 'have truck with' was to barter or do business' with. In the 17th century and onward, the meaning of 'truck' was extended to include 'association'/'communication' and 'to have truck with' then came to mean 'commune with'.

'Truck' is now usually only heard in the negative and this usage began in the 19th century. To 'have no truck with' came to be a general term for 'have nothing to do with'. An example of that is cited in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1834:—

Theoretically an officer should have no truck with thieves.

'Trucking' was also country slang for 'courting'/'dallying with' (and no, in case you are wondering, it has nothing to do with any similar word beginning with 'f'). To 'have no more truck' meant that a courtship had ceased. An example of that usage in print is found in Notes and Queries, 1866:—

[In Suffolk] A man who has left off courting a girl, says that he has 'no more truck along o'har'.

We are a dying breed

According to a study conducted in late April by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Literacy, 32 million adults in the U.S. can't read. That's 14 percent of the population. 21 percent of adults in the U.S. read below a 5th grade level, and 19 percent of high school graduates can't read.

The current literacy rate isn't any better than it was 10 years ago. According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (completed most recently in 2003, and before that, in 1992), 14 percent of adult Americans demonstrated a "below basic" literacy level in 2003, and 29 percent exhibited a "basic" reading level.

According to the Department of Justice, "The link between academic failure and delinquency, violence, and crime is welded to reading failure." The stats back up this claim: 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally illiterate, and over 70 percent of inmates in America's prisons cannot read above a fourth grade level, according to BeginToRead.com.

If anyone reads books, it's probably people who read this material. According to statistics, you're a dying breed:—

• One-third of high school graduates never read another book for the rest of their lives.

• 42 percent of college graduates never read another book after college.

• 80 percent of U.S. families did not buy or read a book last year.

• 70 percent of U.S. adults have not been in a bookstore in the last five years.

• 57 percent of new books are not read to completion.

Pop Vocab

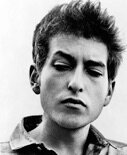

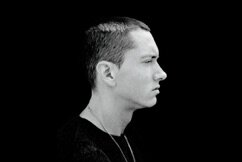

He may be the most revered wordsmith in the classic rock pantheon, but Bob Dylan doesn’t have the widest vocabulary in pop. Far from it, in fact. A study by musixmatch has looked at the numbers of words used in song by 93 of the best-selling artists of all time, as listed by Wikipedia, and discovered that Dylan comes only fifth.

The study looked at the 100 densest songs – by total number of words – in each of the artists’ catalogues, and discovered that the artist with the greatest vocabulary is Eminem, with a vocabulary size of 8,818 words. On average, he uses a word he has never previously used every 11 words. He’s followed by Jay Z (6,899), Tupac Shakur (6,569) and Kanye West (5,069). Dylan lags behind in fifth (4,883).

The places from 7-10 are occupied by four acts for whom English is not a first language: Julio Iglesias, Andrea Bocelli, Celine Dion and B’z. There are surprises elsewhere, too. The best-selling act of all time, the Beatles, are only 76th in the list, with a vocabulary of 1,872 words. The Who, whose Pete Townshend is famed for his songwriting and his rock operas, come in 86th, with 1,794 words, behind Shania Twain and New Kids on the Block.

The average vocabulary size is 2,677 words, with 40 of the 93 artists having a vocabulary size of within 400 words of that total.

Word Rant

by: A journalist from The Guardian, UK

to wed: Who else but journalists would use this ridiculous, archaic word? Imagine a friend telling you, “Hey, I’ve got some great news! Zoe and I are to wed next week.” You would bite your lip, while wondering if they had swallowed the Hello! style guide. The word was almost bearable when it skulked in the red tops; in a serious newspaper (the Guardian, too, is guilty), it is irretrievably naff.

haitch: The eighth letter of the alphabet is pronounced “aitch”. Look it up in a dictionary if you don’t believe me. I challenge you to find an “h” sound in the pronunciation shown there. People born from the 1980s onwards apparently favour this pronunciation; youth is no excuse for illiteracy.

achingly: Here’s another piece of journalistic flimflam, eg “They consistently produce achingly hip music.” Oh, for heaven’s sake, grow up! It isn’t “achingly” anything, you pretentious scribbler. You’re just trying to show how “edgy” (there’s another one) you are.

in terms of: This hook on which many a sentence dangles, gasping for life, is not exactly new, but it is still as irritating and meaningless as ever. A politico says: “We have made great progress in terms of the deficit.” No, we have not.

to leverage, leverage (noun): Business speak has its place, and that place is in business. When TV’s Mr Selfridge intones dramatically, “I don’t want you using my daughter as leverage,” he might sound businesslike; he also shows that the scriptwriter has cloth ears.

unacceptable: Such a feeble, euphemistic little word, but so often trotted out. Little Tommy’s behaviour is “unacceptable”, the kindergarten warns us. What does that mean? Is he behaving like an egocentric monster and, if we don’t do something, will develop into a fully fledged psychopath? Or has he merely pulled Miranda’s hair? A multitude of sins are covered, but never specified, because we are too kind-hearted, too polite and ultimately, too soft.

to address: People in the business of not really meaning what they say love this word for its soothing vagueness. When they undertake to “address the issue of … ” you can be sure that nothing much will happen, and that said issue will speedily be kicked into the long grass. When someone says, “But the government should consider how it could address public concerns,” you can be sure that some kind of perfunctory “listening exercise” will be trumpeted, and then said concerns will be blithely ignored.

a criteria: “Such a criteria is unscientific and misleading.” On reading that my reaction is: “Such a sentence is illiterate and misshapen.” The word is criterion in the singular, and criteria in the plural. Punto e basta!

clamber: eg “Eager crowds clambered to catch a glimpse of the newly elected … ” Unless they turned into Spiderman and shimmied up lamp posts, they did no such thing. What they did was to noisily express (yes, it’s fine to split an infinitive) their eagerness to “catch a glimpse”. In other words, they clamoured.

reach out: Last, and very definitely not least, this absurdly gushing and pseudo-empathetic American metaphor needs no comment. I am sure readers will happily supply their own.

PS: But just as much as these, I detest it when Word’s schoolmistressy grammar checker pedantically and anachronistically warns me that I am ending a sentence with a preposition. I know, you foolish software, and I’m sticking to my guns. That’s how English works.

Murcan splained for Forns

Iowans will tell you they come from Iwa

In Ohio its Hia

People from Milwaukee say they are from Mwawkee

In Louisville its Loovul

In Newark its Nerk

In Indianapolis its Naplus

People from Philadelphia don’t come from there, they come from Fuhluffia

and up in Canada the people from Toronto come from Tronna

But Baltimore wins the prize for slurring (Baltimore pronounced Balamer)

An eagle there is an iggle

A tiger a tagger

Water is wooder

A power-mower is a paramour

A store is a stewer

Clothes are clays

Orange juice is arnjoos

A bureau is beero

And the Orals are the local baseball team.

[With thanks to Bill Bryson’s “The Mother Tongue” for these observations]

Heights of dumbth

A man buying lottery tickets next to me at a counter couldn’t decide on which new type to try, and in the end gave up, saying he would just take his usual kind because otherwise it would be a waste of all the money he has put into that brand. The person serving him said, ‘that’s right.’

A survey came out this week which said that 25% of citizens in the US think the sun goes around the earth.

I don’t know if that 25% is contiguous with the 20% of students who do not graduate from High School, but one graduates from 12th grade, and this is 6th grade material.

Here are clues to what’s wrong and why we should never defund the library:‑

Fifty-three percent of 4th graders report that they read for fun on their own “Almost Every Day.” Among 8th graders, only 20 percent report reading for fun on their own “Almost Every Day” (NCES, 2009).

Forty-three percent of adults read at or below the “Basic” level. This accounts for roughly 93 million individuals (NAAL, 2003).

Where parent involvement is low, the classroom mean average is 46 points below the national average. Where involvement is high, classrooms score 28 points above the national average—a gap of 74 points (NEA, 2009).

Less than half of families read to their kindergarten-age children on a daily basis (West et al., 2000).

And The Moral Is: All these people vote having received the most expensive public education in the world. Literacy, like other arts, is not icing on the cake, it is the cake of democratic life. While US education ranks 17th in the world, it shows no signs of changing any of the statistics above by itself — primary factors have to do with parenting not schooling. The number of students doing Home Schooling are up, and the key to all is literacy.

Hurricane is a native American word, Typhoon is Greek

The word typhoon, which is used today in the Northwest Pacific, may be derived from Arabic ţūfān (طوفان) (similar in Hindi/Urdu and Persian), which in turn originates from Greek Typhon (Τυφών), a monster from Greek mythology associated with storms. The related Portuguese word tufão, used in Portuguese for typhoons, is also derived from Typhon. The word is also similar to Chinese "táifēng" (Simplified Chinese: 台风) (fēng = wind), "toifung" in Cantonese (Traditional Chinese: 颱風), "taifū" (台風) in Japanese, and "taepung" (태풍) in Korean.

The word hurricane, used in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, is derived from huracán, the Spanish word for the Carib/Taino storm god, Juracán. This god is believed by scholars to have been at least partially derived from the Mayan creator god, Huracan. Huracan was believed by the Maya to have created dry land out of the turbulent waters. The god was also credited with later destroying the "wooden people", the precursors to the "maize people", with an immense storm and flood. Huracan is also the source of the word orcan, another word for a particularly strong European windstorm.

Ombudsman, as understood in New Zealand

A recent review of some New Zealand office records revealed some fascinating derivatives from that Swedish

word “Ombudsman.” Communications have arrived, eventually, addressed not surprisingly to the

‘Omnibusman.’

Some came to the confused but politically correct ‘Onwards Person’ or the ‘Office of the Ombudswoman.’

Still, if she missed the office being renamed, ‘Your Honour Sir Nadja Tollemache’ had her supporters for

high honours. One correspondent got the constitutional position right, at least, by writing to ‘The Hon

Busman (Elected by Parliament).’

Another believed Sir Guy Powles suffered from status confusion, writing to ‘The Secretary, Sir Guy

Powlas, House of Lords.’ Some apparently thought the Office enjoyed a larger and more diverse staff

than is the case – one writing to ‘The Manager, Parks Department, Office of the Ombudsman.’ Could an

‘Ombswoodsman’ see the forest for the trees?

One thought Sir George Laking was a cool Jamaican – an ‘On Badsmon’ – while others, perhaps State

servants, distrusted ‘Colonel Powles’ and Sir John Robertson as being ‘Ambushmen.’ There were some

who saw a promising future for an ‘Onwardsman,’ others who anticipated the ‘OdBusman’s’ future in

public transport, or the ‘Od Goods Man’s’ in pre-loved furniture.

Yet more appreciated the integrity of the ‘Omgoodsman,’ the superlativeness of the ‘Ombestman,’ and

the collegiality of the ‘Onboardsman.’ The ‘Ombudisam’ and ‘Onbassum’ have a more oriental than

Nordic ring.

More personally, Sir Guy was a ‘Pal’ to one, conducted ‘Polls’ to another, and was a ‘Pole’ to others, but

surely not ‘Sir Gay,’ ‘Sir Goy’ or ‘Sir Guy Fawkes.’ ‘Sir Brain Elwood’ (an intelligent entomologist?)

was an ‘Onbugsnam.’ Anand Satyanand, perhaps confused with the the tv-advertised producer of Ceylonese

tea, received one communication containing a request for ‘Tea for Two,Two for Tea and no suger please.’ In a confusion not only of tasks but of offices, Judge Satyanand has also been addressed as ‘the bonking Ambudsman.’

Even the personal appearance of the ‘Oubaldsman’ has not been safe. Foreigners not aware that New Zealand has two official languages have sought ‘ Mr Tangata’ – beguiled by the Maori name on the Office’s letterhead.

— this article submitted by Rob Mitchell.

Aural, Oral, Verbal, Spoken

What is it to be? When an NPR reporter can say of a Supreme Court ruling: “...now we shall see what the oral reports will be...” we are certainly mixing our matadors!

Aural relates to hearing; Oral, ‘of the mouth’; Verbal and Spoken reference speech, and a choice whether you like Latin or English terms.

But you cannot ‘see’ any of these.

Khaleesis replacing Amelias? Not hardly.

Worried about naming your child Khaleesi — Perhaps she will sue you in twenty years? Far safer to stick with Amelia. When it comes to popular baby names, Amelia has held the top spot since 2011.

At last count there were only 146 Khaleesis in the US, compared to five in 2010. In 2013 in the UK there were 50 Khaleesis and 11 Theons.

And as for Bilbo, I found this letter on an on-line baby-naming site:—

“I'm having a baby in four months and I really want to name it (me and my hubby have decided to not find out the gender) after my favorite character in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. If it's a boy his name will be Bilbo, if a girl her name will be Bilba. The middle name will be Baggins and the last name is Smithy.

The only problem is that my husband is totally against the name -he thinks we should name the baby Frodo (with the same middle name) And my parents and parents in law are ranting and raving about how ridiculous they think I am being (ironically, this is one of the few times they have agreed).

What should I do? How do I convince my family and hubby that this is the best name for the baby?”

“like a crab going to Ireland”

Words from Devon or are they from Cornwall?

A NEW book on Devon dialect has shone the spotlight on some of the Westcountry's most weird and wonderful phrases.

Devon Dialect, written by language enthusiast Ellen Fernau, based in Norfolk, identifies some of the quirkiest words to be used in our neighbouring county.

Did you know that someone being silly is 'maze as a brush', an 'angletwich' is a fidgety child, and a 'dummon' is an afectionate term for a wife?

A statement from the publisher, Bradwell Books, said: “Devon has a unique set of vocal traditions, many developed because of quirks of geography and others from a complex social demography.

“Many efforts have been made to record the language traditions of the area and to identify the sources of some of the words that are, or used to be, in common use.”

WEIRD AND WONDERFUL DEVONSHIRE WORDS

1. An ‘angletwich’ is a fidgety child or quick moving creature;

2. A ‘dummon’ is an affectionate (we hope) term for wife;

3. Devonians refer to holidaymakers as ‘grockles’ (in Cornwall they are known as ‘emmits’)

4. If you have been cheated, you have been ‘folshid’;

5. A ladybird is, rather grandly, a ‘god's cow’;

6. If you are being silly you are ‘maze as a brush’;

7. Or, if you have no sense, you have ‘no nort’;

8. And nonsense is ‘witpot’;

9. While the word for daft is ‘zart’;

-

10.Charmingly, ‘snishums’ is the Devon word for sneezing.

The book has prompted a flurry of responses from people in Devon offering words of their own as part of their dialect - but are these Cornish terms?

Louise Tuttiett recollects 'Chiggy pig' being used for a woodlouse.

Leigh Morgan claims “dreckley”, as in “I’ll be there dreckley” is a Devon term.

Chloe Nichols reminded us of the saying “ark at ‘ee!”

Lily-Beth Chugg said that “tiffle” is a bit of thread coming off your clothes.

Penina Stanway said she often says “maze as brish”, "Wat ee catch last night, ort or nort?", "spuds" or "teddies" and that ladies are "maids”. She added that she had just had a conversation about “Chiggy pigs” and introduced us to “Tis ansome. Twas.”

And her four-year-old sings "I am a zider drinker".

Clothes can be on “backsyvore” or “skew-whiff”, handwriting can de critiqued as being “like a crab going to Ireland” and that after a hard day you can be “gone like a long-dog”.

Foxgloves are “floppydocks”, stitchworts are “whitsundays”, thistles are “dashels” and couch grass is “stroil”.

Unique words for training farm horses include “giddup”, “come’yer”, “wug-off”, “back-back” and “whoa”.

Describing distance using one, two or three “gunshots” was once common in these parts, and if further away it was “a jaunt for a fox”.

Children would be sent up “Timburn Hill” for “a bit of shut-eye” when “dimpsey” – twilight – had arrived.

If you are amused you might “laugh like a pixie”, but when all in a muddle you are “fair mazed”.

Death is also treated with warm humour, with a coffin described as a “wooden overcoat”.

Jim Bullard said: "When I first arrived in Devon Many years ago I was always greeted with 'ow be nackin vor boey?', which of course means 'how are you doing?'

"The answer being; 'brave ‘n vitty' or 'master vine', meaning very well.

"The most well-known phrases however are probably; 'get out aye' and 'proper job you'."

Drakonian

Draco (/ˈdreɪkoʊ/; Greek: Δράκων, Drakōn) (circa 7th century BC) was the first legislator of Athens in Ancient Greece. He replaced the prevailing system of oral law and blood feud by a written code to be enforced only by a court. Draco's written law became known for its harshness, with the adjective draconian referring to similarly unforgiving rules or laws.

Drakonian also relates a folkloric story of his death in the Aeginetan theatre. In a traditional ancient Greek show of approval, his supporters "threw so many hats and shirts and cloaks on his head that he suffocated, and was buried in that same theatre".

The laws (θεσμοί - thesmoi) he laid down were the first written constitution of Athens. So that no one would be unaware of them, they were posted on wooden tablets (ἄξονες - axones), where they were preserved for almost two centuries, on steles of the shape of three-sided pyramids (κύρβεις - kyrbeis). The tablets were called axones, perhaps because they could be pivoted along the pyramid's axis, to read any side.

The constitution featured several major innovations:

Instead of oral laws known to a special class, arbitrarily applied and interpreted, all laws were written, thus made known to all literate citizens (who could make appeal to the Areopagus for injustices): "... the constitution formed under Draco, when the first code of laws was drawn up." (Aristotle: Athenian Constitution, Part 5, Section 41)

The laws distinguish between murder and involuntary homicide. The laws, however, were particularly harsh. For example, any debtor whose status was lower than that of his creditor was forced into slavery.[citation needed] The punishment was more lenient for those owing debt to a member of a lower class. The death penalty was the punishment for even minor offences. Concerning the liberal use of the death penalty in the Draconic code, Plutarch states: "It was a lot for himself, when asked why he had fixed the punishment of death for most offences, answered that he considered these lesser crimes to deserve it, and he had no greater punishment for more important ones."

All his laws were repealed by Solon in the early 6th century BC, with the exception of the homicide law

Descriptive or Prescriptive?

This brings me to the descriptive v prescriptive argument. For at least 50 years almost all academic linguistics has been descriptive, concerning itself with how language is structured and used without passing judgment on what is right or wrong. Lexicographers, similarly, work by establishing that a word is in use with a particular meaning. If it does, they will put it in the dictionary and ignore the howls of protest from those who think this is providing respectable cover for the barbarians who want to wreck our beautiful language.

Does this mean that things are getting worse? Lynne Truss, who wrote a book about punctuation, typified such fears when she referred to "the justifiable despair of the well educated in a dismally illiterate world". According to this argument, it all started to go wrong in the 1970s "when teachers upheld the view that grammar and spelling got in the way of self-expression".

People have been wittering on like this for centuries. Conservatives long for a golden age, usually about 50 years in the past, when everyone knew their grammar and all was right with the world. "What is more, even Grammar, the basis of all education, baffles the brains of the younger generation today ... There is not a single modern schoolboy who can compose verses or write a decent letter" – not Michael Gove, but William Langland (born 1332!). Sadly, there never was a golden age. The privately educated actor Dirk Bogarde described his astonishment when he joined the army in the 1940s on finding that all the men in his platoon, who were state educated, were in effect illiterate. Yet this was the era when, according to Truss, most people did "know how to write". I attended a grammar school as one of the top 10% or so who passed the 11-plus. Even among this elite, many took little interest in English grammar and even those who did had forgotten most of it by the time they got to university. We had to take a Use of English exam in between O-level and A-level to address concerns over – you guessed it – declining standards. So much for the golden age.

For their part, academics have a pretty poor record of explaining descriptive linguistics to the public and can come across as aloof and arrogant. (There are exceptions, such as the great David Crystal.) Can there ever be peace, when the two sides are so entrenched? Or must they for ever be in conflict, like the farmer and the cowman in Oklahoma!? I'd like to think there is a middle way that doesn't condemn but does help people to gain confidence in their use of language. I am not arguing that everything is perfect; far from it. But there's no sound evidence that standards are worse than when Lynne Truss and I were at school. And rather than blame it all on teachers and the national curriculum, the why-oh-why-are-things-so-awful-it-was-so-much-better-in-my-day lobby might wonder why it is that many of the worst language abuses come from people who have actually been well (often expensively) educated: politicians and business people, for example. It's not schoolchildren who spout drivel like "change that makes a difference for hardworking families" and "owning the strategic roadmap for the goods-buying platform".

This is an edited extract from For Who the Bell Tolls: One Man's Quest for Grammatical Perfection, by David Marsh (Guardian Faber)

Pew Report on Reading

"The details of the Pew report are quite interesting and somewhat counterintuitive. Among American adults, women were more likely to have read at least one book in the last 12 months than men. Blacks were more likely to have read a book than whites or Hispanics. People aged 18-29 were more likely to have read a book than those in any other age group. And there was little difference in readership among urban, suburban and rural population."

“The Pew Research Center reported last week that nearly a quarter of American adults had not read a single book in the past year. As in, they hadn’t cracked a paperback, fired up a Kindle, or even hit play on an audiobook while in the car. The number of non-book-readers has nearly tripled since 1978.”

From “Reading Books is Fundamental” by Charles M. Blow, from the Opinion Pages of The New York Times, January 22, 2014

The first thing I can remember buying for myself, aside from candy, of course, was not a toy. It was a book. It was a religious picture book about Job from the Bible, bought at Kmart.

It was on one of the rare occasions when my mother had enough money to give my brothers and me each a few dollars so that we could buy whatever we wanted. We all made a beeline for the toy aisle, but that path led through the section of greeting cards and books. As I raced past the children’s books, they stopped me. Books to me were things most special. Magical. Ideas eternalized.

Books were the things my brothers brought home from school before I was old enough to attend, the things that engrossed them late into the night as they did their homework. They were the things my mother brought home from her evening classes, which she attended after work, to earn her degree and teaching certificate.

Books, to me, were powerful and transformational.

So there, in the greeting card section of the store, I flipped through children’s books until I found the one that I wanted, the one about Job. I thought the book fascinating in part because it was a tale of hardship, to which I could closely relate, and in part because it contained the first drawing I’d even seen of God, who in those pages was a white man with a white beard and a long robe that looked like one of my mother’s nightgowns.

I picked up the book, held it close to my chest and walked proudly to the checkout. I never made it to the toy aisle.

That was the beginning of a lifelong journey in which books would shape and change me, making me who I was to become. We couldn’t afford many books. We had a small collection. They were kept on a homemade, rough-hewn bookcase about three feet tall with three shelves. One shelf held the encyclopedia, a gift from our uncle, books that provided my brothers and me a chance to see the world without leaving home.

The other shelves held a hodgepodge of books, most of which were giveaways my mother picked when school librarians thinned their collections at the end of the year. I read what we had and cherished the days that our class at school was allowed to go to the library — a space I approached the way most people approach religious buildings — and the days when the bookmobile came to our school from the regional library.

It is no exaggeration to say that those books saved me: from a life of poverty, stress, depression and isolation.

James Baldwin, one of the authors who most spoke to my spirit, once put it this way:

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me the most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

That is the inimitable power of literature, to give context and meaning to the trials and triumphs of living. That is why it was particularly distressing that The Atlantic’s Jordan Weissmann pointed out Tuesday that:

“The Pew Research Center reported last week that nearly a quarter of American adults had not read a single book in the past year. As in, they hadn’t cracked a paperback, fired up a Kindle, or even hit play on an audiobook while in the car. The number of non-book-readers has nearly tripled since 1978.”

The details of the Pew report are quite interesting and somewhat counterintuitive. Among American adults, women were more likely to have read at least one book in the last 12 months than men. Blacks were more likely to have read a book than whites or Hispanics. People aged 18-29 were more likely to have read a book than those in any other age group. And there was little difference in readership among urban, suburban and rural population.

I understand that we are now inundated with information, and people’s reading habits have become fragmented to some degree by bite-size nuggets of text messages and social media, and that takes up much of the time that could otherwise be devoted to long-form reading. I get it. And I don’t take a troglodytic view of social media. I participate and enjoy it.

But reading texts is not the same as reading a text.

There is no intellectual equivalent to allowing oneself the time and space to get lost in another person’s mind, because in so doing we find ourselves.

Take it from me, the little boy walking to the Kmart checkout with the picture book pressed to his chest.

Reader’s Rights

Here lies a dark wood: The condition of reading is onerous in schools — the compulsion to have to make a report, to have to answer other people’s questions, to have to do it quickly without time to digest and reflect, even to have to read the book in the first place. These strategies seem to smother the love of it. In Finland they have thrown away all the 'American' obsessive needs to measure, and simply gone for creativity, and they are now #1 educators in the world. Perhaps this also has to do with a shifted emphasis from Teaching to Learning?

Meanwhile here in the USA the sorry and unnatural story goes like this — our good intentions have achieved this:

Here is a Bill of Reader’s Rights composed by Daniel Pennac

1. The right to not read

2. The right to skip pages

3. The right to not finish

4. The right to reread

5. The right to read anything

6. The right to escapism

7. The right to read anywhere

8. The right to browse

9. The right to read out loud

10. The right to not defend your tastes”

Baited Breath

Preamble — I had been joking with Mac Gander about seeing a student’s spelling, ‘baited-breath,’ and made some tuna jokes. Then I missed putting up his column and he wondered if I didn’t like it? Here is the response:

Laugh — hardly that. It's hard to think what I would suppress — possibly really long golf anecdotes? But you are to consider, the folks who edited the bible did the same.

I think there was some sort of coincidence that I put up in the column 'Passages' an item on memory and probably threw away your text with mine. This itself is a joke on memory.

Apropos of nothing, The Guardian UK also committed to the spelling 'baited-breath' recently.

I looked it up: From Italian abate, from Latin abbās, abbātis, from Ancient Greek ἀββᾶς ( abbas), from Aramaic אבא ('abbā, “father”).

But not evidently 'that' father. The word 'God' interestingly is none of these, but Indo-European, or Gothic, from 'Guth' which has a meaning rendered, 'sound of the air lessening.'

I suppose this is too wide to connect with memory, except poetically, as if the lessened billows allows memory rather than any excitation of current senses.

Changing senses

New words in the culture, something borrowed something new:—

DEFACED: To withdrawn from Facebook usually in a huff

REFACED or SHAMEFACED: To quietly re-enter Facebook, usually no more than a month later.

Perhaps readers can do better, or if they don’t like the challenge above, they could try SUPER as a prefix and invent a S/Hero such as SUPERSIZEMAN; he absorbs fats from the environment and sucks up toxins just by being in the neighborhood. Beat that!?

Honky

I had always thought that the word 'honkies' was a Native American aspersion on the way the Pilgrims spoke, that is, with a hard metallic nasal twang, not unlike geese, but no, Wikipedia says:—

Honky may derive from the term "xonq nopp" which, in the West African language Wolof, literally means "red-eared person" or "white person". The term may have originated with Wolof-speaking slaves brought to the US.

Honky may also be a variant of hunky, which was a deviation of Bohunk, a slur for Bohemian-Hungarian immigrants in the early 1900s. Honky may have come from coal miners in Oak Hill, West Virginia. The miners were segregated; blacks in one section, whites in another. Foreigners who could not speak English, mostly from Europe, were separated from both groups into an area known as "Hunk Hill". These male laborers were known as "Hunkies."

Another documented theory, and possible explanation for the origins of the word, is that honky was a nickname black people gave white men (called "johns" or "curb crawlers") who would honk their car horns and wait for prostitutes to come outside in urban areas (such as Harlem and red-light districts) in the early 1910s.

The term may have begun in the meat packing plants of Chicago. According to Robert Hendrickson, author of the Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins, black workers in Chicago meatpacking plants picked up the term from white workers and began applying it indiscriminately to all whites. "Father of the Blues" W.C. Handy wrote of "Negroes and hunkies" in his autobiography.

Honky was adopted as a pejorative in 1967 by black militants within Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) seeking a rebuttal for the term nigger. National Chairman of the SNCC, H. Rap Brown, on June 24, 1967, told an audience of blacks in Cambridge, "You should burn that school down and then go take over the honkie's [sic] school." Brown went on to say: "[I]f America don't come 'round, we got to burn it down. You better get some guns, brother. The only thing the honky respects is a gun. You give me a gun and tell me to shoot my enemy, I might shoot Ladybird."

Honky has occasionally (and ironically) been used even for whites supportive of African-Americans, as seen in the 1968 trial of Black Panther Party member Huey Newton, when fellow Panther Eldridge Cleaver created pins for Newton's white supporters stating "Honkies for Huey."

In Australia, Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong itself, the term is used in a casual nature to refer to people originating from Hong Kong.

It may also be a familiar short form for Ukrainian: Гончаренко ("Honcharenko"), which is a common Ukrainian last name, sometimes transcribed as Honcarenko instead of Honcharenko. It has been used in Canada, the U.S. and Australia to refer to a person of Ukrainian origin.

The Oxford English Dictionary states that the origin of the term honky tonk is unknown. The earliest source explaining the derivation of the term was an article published in 1900 by the New York Sun and widely reprinted in other newspapers, such as the Reno Evening Gazette (Nevada), 3 February 1900, pg. 2, col. 5. "Every child of the range can tell what honkatonk means and where it came from. Away, away back in the very early days, so the story goes, a party of cow punchers rode out from camp at sundown in search of recreation after a day of toil. They headed for a place of amusement, but lost the trail. From far out in the distance there finally came to their ears a 'honk-a-tonk-a-tonk-a-tonk-a,' which they mistook for the bass viol. They turned toward the sound, to find alas! a dock [sic] of wild geese. So honkatonk was named. N. Y. Sun.

New Words in the OED

Last year

omnishambles was voted the word of the year by the Oxford English Dictionary.

Some of the more

vom-worthy (vom: v. & n. informal: (be) sick; vomit) creatures of the digital undergrowth have also made the new edition, including

selfie (a photograph taken of oneself, typically with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website);

unlike (v. withdraw one's liking or approval of a web page or posting on a social media website that one has previously liked);

phablet (smartphone having a screen which is intermediate in size between that of a typical smartphone and a tablet computer); the dreaded

"internet of things" (proposed development of the internet in which everyday objects have network connectivity, allowing them to send and receive data); and the much needed

"digital detox" (a period of time during which a person refrains from using electronic devices such as smartphones or computers, regarded as an opportunity to reduce stress or focus on social interaction in the physical world).

Keep at bay

What does this phrase mean? (Answer at foot of column) I thought this might be an interesting quiz so suggest three possible origins:—

-

1)Baying is a continuous barking by hounds. To keep something at bay means to prevent its escape by surrounding it with barking dogs, or by extension, to prevent a problem from getting out of control by maintaining constant vigilance.

-

2)An abbreviated form of embay, or to enclose within a bay as result of storm and prevailing winds, and also a specific in restriction of an opponent’s navy such as Britain did to the French fleets in the Napoleonic era.

-

3)“The refreshment of meats”, a seventeenth century term used to disguise the odor of gone-off or dodgy meat with herbs and spices, especially sage and bay leaves.

You say tomato

Anglo Saxon consists of 3 language groups, Mercian, West Sussex [or Wessex] and Norse spoken in the Danelaw. Here are common words from ‘English’ or wessex and Norse, which ones do you use?

English/Wessex Norse/East Anglia

Rear Raise (a child)

Wish Want

Craft Skill

Hide Skin

And here are two versions of the sentence

“have you horses for sale”

haefst thuy hors to sellene (Wessex)

hefir thu hross at selja (Norse)

Wuthering

The annual street market in the village and I take out piles of stuff for the junk stall. At home this clearing-out process was always known as ‘wuthering’ and Dad used to love it. ‘What’s happened to such and such?’ I would ask Mam. ‘Ask your Dad. He’s probably wuthered it.’

— Diary entry, 27 July 1986, Alan Bennett (from his title, ‘Writing Home’)

The devil to pay

Earlier in the week I overheard, ‘pitched-black.,’ which of course is a misapprehension of ‘pitch-black’ and these two terms are related as explained by Patrick O’Brian and others:—

The 'devil' is a seam between the planking of a wooden ship. Admiral William Henry Smyth defined the term in The Sailor's Word-book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms, 1865:

Devil - The seam which margins the waterways on a ship's hull.

'Paying' is the sailor's name for caulking or plugging the seam between planking with rope and tar etc. 'Paying the devil' must have been a commonplace activity for shipbuilders and sailors at sea. This meaning of 'paying' is recorded as early as 1610, in S. Jourdain's Discovery of Barmudas:

Some wax we found cast up by the Sea... served the turne to pay the seames of the pinnis Sir George Sommers built, for which hee had neither pitch nor tarre.

Many sources give the full expression used by seafarers as "there’s the devil to pay and only half a bucket of pitch", or "there’s the devil to pay and no pitch hot".

The article just cited goes on to doubt an original naval origin but not citing any authority though indicating an C17th one, but does not regress enough, so I spare the reader it’s digressions.

Much older use of the word occurs in two citations from the word DEVELING; laying flat, and are easily understood thereby to laying ship’s boards flat by use of tar, rather than them buckling. See Arthour and Merlin, p. 287, and Beves of Hamptoun, p. 27. Which is sometimes spelled Bevis of Hampton, written c. 1324.

The first reference is after Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written c. 1136.

Parcel

My wife said that a box had arrived by UPS. I went outside and didn’t see one, then I found it, a book from Amazon. Reentering the house I said that a box in England was something perhaps 2 feet by 3, though nothing so exact. What would you call this other than box? She said a package. I said I remember this being a parcel, then I looked it up.

parcel (n.)

late 14c., "a portion of something, a part" (sense preserved in phrase parcel of land, c.1400), from Old French parcele "small piece, particle, parcel," from Vulgar Latin *particella, diminutive of Latin particula "small part, little bit," itself a diminutive of pars (genitive partis) "part" (see part (n.)).

Meaning "package" is first recorded 1640s, earlier "a quantity of goods in a package" (mid-15c.), from late 14c. sense of "an amount or quantity of anything." The expression part and parcel (early 15c.) also preserves the older sense; both words mean the same, the multiplicity is for emphasis.

parcel (v.)

"to divide into small portions," early 15c. (with out), from parcel (n.). Related: Parceled; parcelled; parceling; parcelling.

Sough

sough (sou, sf)

intr.v. soughed, sough·ing, soughs

To make a soft murmuring or rustling sound.

n. A soft murmuring or rustling sound, as of the wind or a gentle surf.

[Middle English swowen, soughen, from Old English swgan.]

soughing – A soft rustling or murmuring sound—like the deep sigh of a sleeping baby.

Adj. soughing - characterized by soft sounds; "a murmurous brook"; "a soughing wind in the pines"; "a slow sad susurrous rustle like the wind fingering the pines" — R.P.Warren

Eleventy-one

English, like many other Germanic languages, retains traces of a base-12 number system. The most obvious instance is eleven and twelve which ought to be the first two numbers of the "teens" series. Their Old English forms, enleofan and twel(eo)f(an), are more transparent: "leave one" and "leave two."

[Viking survivors who escaped an Anglo-Saxon victory were daroþa laf "the leavings of spears," while hamora laf "the leavings of hammers" was an Old English kenning for "swords," both from "Battle of Brunanburgh."]

Old English also had hund endleofantig for "110" and hund twelftig for "120." One hundred was hund teantig. The -tig formation ran through 12 cycles, and might have bequeathed us numbers *eleventy ("110") and *twelfty ("120") had it endured, but already during the Anglo-Saxon period it was being obscured.

Older Germanic legal texts distinguished a "common hundred" (100) from a "great hundred" (120). Old Norse used hundrað for "120" and þusend for "1,200." Tvauhundrað was "240" and þriuhundrað was "360." This duodecimal system, according to one authority, is "perhaps due to contact with Babylonia," an extraordinary suggestion.

Outside Germanic in living Indo-European the only instance of this formation is said to be in deeply conservative Lithuanian, which uses -lika "left over" to make vieniolika "eleven," dvylika "twelve" and continues the series to 19 (trylika "thirteen," keturiolika "fourteen," etc.).

(From the online etymological Dictionary)

Hurr

hurr (v) - [from the OED] - " To make or utter a dull sound of vibration or trilling; to buzz as an insect; to snarl as a dog; to pronounce a trilled 'r'." "1637 B. Jonson Eng. Gram. i. iv, in Wks. (1640) III, R Is the Dogs Letter, and hurreth in the sound."

An older dictionary, Halliwell, says Jonson also has, HURRE: to growl or to snarl, and Shakespeare does HURLY, a noise, or tumult.

Salutory

I found myself writing non-salutory but the spell-checker in the program didn’t like the word, and so I Googled it, and it doesn’t exist! That is to say, people use, and are understood, but ‘salutory’ does not exist in any dictionary. Therefore, if you had to make a dictionary entry, what would you write.

Redact

transitive verb

1 : to put in writing : frame

2 : to select or adapt (as by obscuring or removing sensitive information) for publication or release; broadly : edit

3: to obscure or remove (text) from a document prior to publication or release

Origin of REDACT

Middle English, from Latin redactus, past participle of redigere

First Known Use: 15th century

Someone else has a go at it with:—

To redact is to edit, or prepare for publishing. Frequently, a redacted document, such as a memo or e-mail message, has simply had personal (or possibly actionable) information deleted or blacked out; as a consequence, redacted is often used to describe documents from which sensitive information has been expunged.

BUT this is not current media use of the term, they use it as ‘take-back’ as if ‘unsay’ rather than moderate or qualify.

And in cahoots with media are politicians who no longer need to apologize for a false statement, only redact it.

UMBRELLA as a verb:

UMBREL: (1) a lattice (2) Same as /umber/ sometimes written /umbrere/. "Keste upe hys umbrere," MS Morte Arthure, f. 63. A clue is from Ubrere to the verb form: UMBE-LAPPE. To suround; to wrap round. And he and his oste umbraylapped alle thaire enemys, and daunge thame doune, and slew thame ilke a moder sone. — MS Lincoln . 1. 17, f. 5 There is also UMBE-CLAPPE as verb: Embrace and UMBE-GRIPPE; to seize hold of. Going back even further the origin appears to be the Anglo Saxon word UMBEN. About; around from which comes UMBE-SET. to set around or about. PLUS! the fantastic word UMBIGOON. Surrounded, which is found in MS. Bodl. 423 f. 186. UMBYLUKE. To look around, MS. Lincoln and UMLAPPE to enfold; to wrap around, which is the word nearest the modern attempt, or possibly UMSETTE. Surrounded, beset. Naturally none of this will appear in the Merriam Webster, nor likely any in the OED. But I would like to campel with anyone who knows any of these words.

One more: From our A.S root~ AMBEN, comes AMBAGE. Circumlocation, Spanish Tragedy, Marlowe's Works, iii. 257. In an old glossary in Ms. Rawl. Poet 108, it is explained by 'circumstance', See Brit. Bibl ii. 618. It is used as a verb, apparently meaning to travel around in Morte d'Arthur i. 135 [Lat] — indeed, we still say 'ambulant' meaning able to get around.

Hobbety

BBC News report:

A popular pub and music venue called The Hobbit has been threatened with legal action by US movie lawyers.

The Southampton pub has been accused of copyright infringement by lawyers representing the Saul Zaentz Company (SZC) in California.

The company owns the worldwide rights to several brands associated with author JRR Tolkien, including The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings.

Landlady Stella Mary Roberts said: "I can't fight Hollywood."

The pub in Portswood, which is popular with students, has traded with the name for more than 20 years.

It features characters from Tolkien's stories on its signs, has "Frodo" and "Gandalf" cocktails on the menu, and the face of Lord of the Rings film star Elijah Wood on its loyalty card.

A letter from SZC asked it to remove all references to the characters.

More, and a short bit of film here http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-17350103

I investigated the word “Hobbit” which I was sure linguist Tolkien would have known, and which in fact he did not coin, since surely the word “Hobbety” would be known to him? And the professor of Anglo Saxon at Oxford would also have know the A. Sax verb HOBELEN. I give some reference and sources below.

HOBBETY-HOY

A lad between boyhood and manhood, “neither a man nor a boy,” as the jingling rhyme has it. Tusser says the third age of seven years is to be kept “under Sir Hobbard de Hoy.” The phrase is very variously spelt. Hobledehoy, Palsgrave’s Acolastus, 1540.

There are other formations upon Hob~ and still in use is Hobgoblin, invoking an Elvish or otherworldly sense, and all likely to stem from the even older word, an Anglo Saxon verb, HOBELEN, To skip over.

These notes are taken from Dictionary of Archaic Words, James Orchard Halliwell, originally published in 1850 by John Russell Smith, London. This edition is © Bracken Books, 1989 and reports on 51,027 words.

Are you a Reactionary?

(In answer to correspondence if there is a difference between freedom and license, here are a few more definitions of what’s what beyond the simpleton terms used in the media; if you are a Liberal or a Conservative)

I have been musing on recent debates about Conservatives and Liberals in the political world, and an inchoate jumbling of terms together as if words have no meanings, and as if those two categories were the only two states of being possible.

I should like the reader to not think about politics while reading a fuller range of descriptions below, and instead think of food habits or vacations.

Reactionary:

Not content with the status quo and prefers to return to a previous high point.

Conservative:

Content with the status quo as is.

Liberal:

Content with the status quo if it can be adjusted.

Radical:

Not content with the status quo, nor any previous high point, and prefers and prefers something completely new.

I know it is very hard not to think ‘politics’ about all these definitions, but try! What if the subject was food, for example?

The Reactionary will not like current eating habits, but might prefer something from the past, of what mother cooked, or grandmother cooked,; the food, the atmosphere in cooking it, and sitting down together to eat it. The Conservative will like however it is these days, some eating out, some buying in, but not typically cooking all from scratch as grandma maybe did above. The Liberal will like eating in and out, but keeping experiments going on menus, tweaking here and there. The Radical will maybe reduce their food intake to 10 items, with no gluten, meat or prepared food — not to be prescriptive of Radical, so maybe reducing food to Steak and Whiskey diet? But to something outside status quo and new.

Get the idea? I hope so since a general survey over a dozen topics reveals this: We are 1 part Reactionary, 2 parts Conservative, 2 parts Liberal, 1 part Radical. This survey is true over all ages, religions, and political orientations.

As usual, words have been hijacked by parties who only want to appeal to one or another possibility, and this only about politics. And this obscures the fact that somewhere you, dear reader, are likely a reactionary, and just as like your neighbor you are also a radical. In some things you are content to be just as you are and conservative, and in others you are content to be changing things a little here and there.

Taken all together we have some sense of the whole person, and not just the coin toss of Liberal:Conservative which fight was done our country more damage than any enemy could wish for.

Additionally these 4 categories are stated by the cultural anthropologist, William Irwin Thompson, to be universal in our times and in all times, in all cultures.

Fech

My wife said, “you know he is often feckless?” Which I readily understood, but what does FECH mean? All these:—

-

1)To kick or plunge

-

2)Many, plenty, quantity

-

3)Might, activity

-

4)A small piece of iron used by miners in blasting rods

FECKFUL: strong, zealous, active

These word originates from the North of England. Current usage is from ‘effectless’ meaning weak or impotent, and likely derived from the Latin FECULA; dregs of wine, sedimentary.

#3 He almost certainly did not do what the PBS documentary suggested, since he would likely have lost if he did. They probably meant eviscerated. Decimate means to reduce by one in ten. The term comes from a punishment in the Roman Legions where 1 in 10 legionnaires were punished, and even put to death, for significant failure in battle.

The ‘F’ word revealed, also Beer and Ale

I wonder if people know the origin of a favorite word, which appears

indifferently as verb, adverb, adjective, the one beginning with 'F'.

It's relatively new to the language and tho’ Chaucer knew it, it was a

couple hundred years later that it caught on in public speech, in

approximate early Elizabethan times [maybe 40 years before in East

Anglia] and an imported Flemish word, which came over with the new

hops — hops which supplanted wild native additives to darken the brew

and add some sort of flavor, and thereby gave us the distinction

between true Ale and the new Beer which latterly included sugar from

slave plantations in the Caribbean. The C word came at the same time.

Remarkably these introductions easily supplanted native speech which

appears to have had no generalized epithets for them, and also supplanted native ale. God save the Germans who resisted adding sugars to speed the beer to market and quickly develop its alcohol content, even to this day.

If you want to try an ale as had in 1600 try a German micro brewery

with up to 15% alcohol — I think, not sure, 17.5% is the maximum you

can do. In England there used to be, maybe still, a 'beer' called

Barley Wine which would blow your socks off — stronger than wine or

Port.

All Texts are Artificial Language

I thought this exchange worth a note:

> > You should try it some time. It will give you the full

> > etymology of your favorite word

> Only you would sit around and read a dictionary. Everyone else just

> consults their dictionary. Get a clue.

The first speaker above is getting a clue, and a good dictionary can read like a history or an anthropological record. It can also display several meanings of any one word, it's origin in place [rather than merely in books], and how by usage it has changed over time. Knowing something of etymology also gives us the ability to read books from even as recently as the past century and understand the context in which the word was used, it now having changed in usage to mean something very different.

The OED uncertainly gives 'full etymology' in large part because of the peculiar system of its composition. There is even one century where American readers were preferred for a specific century because it was thought English readers would not find it to their interest. Other centuries are here and there represented by less extracts from books than previous centuries.

One major 'issue' with the OED's etymology is that it only selected popular books, and this has certain implications for what is included in the dictionary in two respects; obviously a rare MSS or Codex or other book form cannot be sent out of research libraries, and sometimes not even consulted since a private library, scriptorium, etc, doesn't care to share it. It may well be true that an early printed reference may be cited as C13th, but this should not be confused with an etymology, since the word could be, even in English, 700 years older, and early Saxon.

But the main issue is that the OED's words are all from texts — and these texts do not represent the people's speech neither in extent nor proportionally. It is even dangerous to assume that 'English' was any single language, rather than distinct groups of dialectical words from regions of England, to which other areas would not well understand.

Further, in consideration of what people actually spoke <emphasis> words in the OED may not represent them at all. I have for example a rare dictionary of 50,000 words in English which every philologist will have and perhaps no-one else, and these words many of which have not appeared even in scattered glossaries, contain valuable material.

Anyway, that is to provide a background to a complicated subject to which a major American philologist, Mario Pei (1901-1978), suggests that texts are entirely artificial constructs which no one ever spoke. This may explain an extraordinary statement by George Orwell about life in British pubs during World War II. He noticed that the always-on radio received very little attention and concluded that it wasn't just the BBC's 'Oxford' pronunciation that people didn't like, but they didn't even understand it.

ANSWERS:—

Keep at bay

-

1)Baying is a continuous barking by hounds. To keep something at bay means to prevent its escape by surrounding it with barking dogs, or by extension, to prevent a problem from getting out of control by maintaining constant vigilance.